(Expanded version of article published in Winter 2018 issue of California Waterfowl)

(Expanded version of article published in Winter 2018 issue of California Waterfowl)

by CAROLINE BRADY, WATERFOWL PROGRAMS SUPERVISOR

Skip ahead to:

Upland nesting habitat

Predators

Brood water

Molt water

Problems and solutions

Financial assistance

Sources used for this article

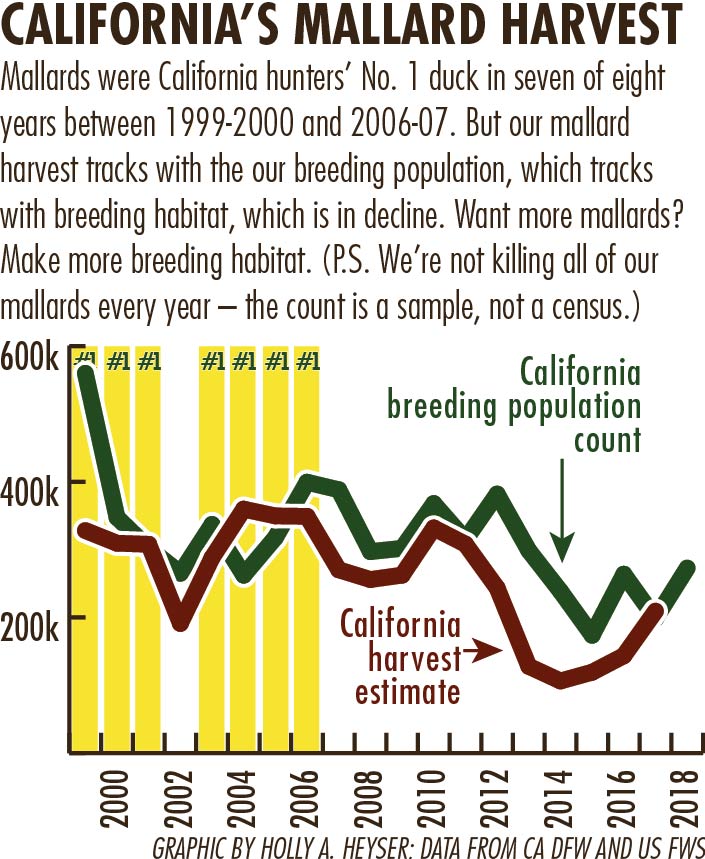

It wasn’t so long ago that California consistently killed more mallards than we do now.

The mallard was our No. 1 bird for seven of eight seasons between 1999 and 2006, according to federal data. Last season was our best mallard season in five years, but we still killed 72% more in 2004-05.

Here’s the frustrating thing: We know what the problem is. We know what the solution is. But we’re just not getting it done.

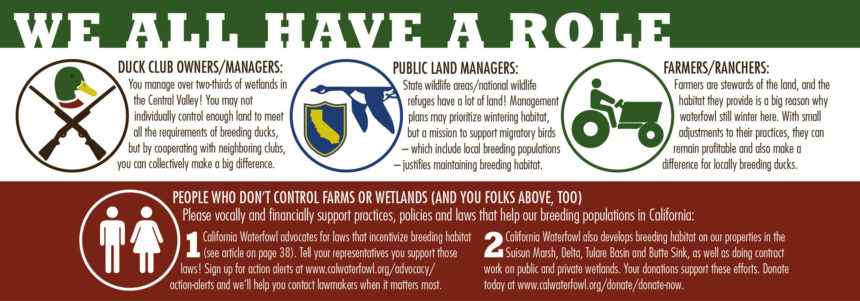

If you like bagging lots of spoonies and gadwalls, carry on. But if you like putting big, iconic greenheads on your strap, there is something every single one of you can do: duck club owners, public wetland managers, farmers and even ordinary hunters who don’t control land-use decisions.

THE PROBLEM

Here’s the deal: We know that about 70% of the mallards we harvest in California hatched in California. Our mallard harvest rises and falls primarily with the California breeding population, not the mid-continent (Prairie Pothole Region) breeding population.

And we know the breeding population in California rises and falls with breeding habitat.

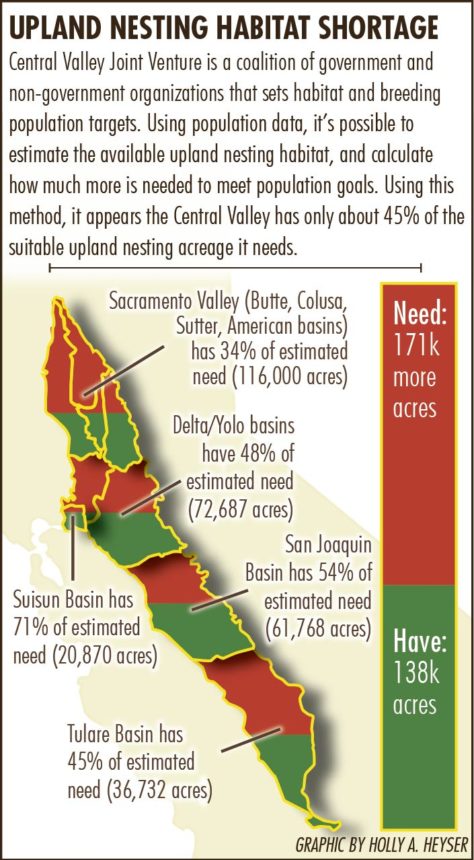

Yet for a variety of reasons, most wetland managers focus on providing habitat for the millions of birds that descend on the state each winter, not for the half-million ducks – predominantly mallards – that stay here in spring and summer to breed, build nests and raise their broods.

That may have worked fine in the past, but now other forces have wreaked havoc on breeding habitat: drought (which we can’t fix), urban development (good luck keeping the human population from growing), a shift to less duck-friendly crops (fruit and nut trees, vineyards, strawberries) and catastrophic federal policy decisions to withhold water from the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, which is a critical breeding and molting area.

California has done an incredible job for the wintering population of ducks. We’ve restored habitat, and the 1990s rice-burning ban led to flooding most rice after harvest, which was great for wintering waterfowl. Studies show we’re sending ducks back to their breeding grounds now in substantially better condition than we were in the 1980s.

Now it’s time to put more effort into our breeding population. In this article, we’re going to tell you what breeding ducks and their broods need, and how we can provide it. We’ll even point you to some funding sources.

Say it with me here, people: The more breeding habitat we have, the more mallards we will have in the bag.

THE SOLUTION: HOW TO MAKE MORE MALLARDS

The basic building blocks of breeding habitat are upland fields suitable for nesting and nearby water suitable for breeding pairs and brood rearing.

GIVE DUCKS A PLACE TO NEST: UPLAND HABITAT

To nest, ducks need sufficient upland habitat, ideally within a mile of a water source: wetlands, rice fields or irrigation ditches/sloughs. Sloughs and ditches are least desirable because they’re filled with predators. The more breeding habitat there is near water, the more hens will attempt to nest, and when habitat is good, California has higher nest densities than the Prairie Pothole Region.

To nest, ducks need sufficient upland habitat, ideally within a mile of a water source: wetlands, rice fields or irrigation ditches/sloughs. Sloughs and ditches are least desirable because they’re filled with predators. The more breeding habitat there is near water, the more hens will attempt to nest, and when habitat is good, California has higher nest densities than the Prairie Pothole Region.

Perennial and annual grasses and forbs are ideal vegetation for nesting. You can go with native or non-native perennial grasses (such as tall wheat grass, fescue).

Forbs (flowering plants) provide more invertebrates (bugs) for birds that have high protein needs, including upland birds. They’re also great for pollinators. Eradicate pepperweed, thistle, mustard and radish – they’re not beneficial, and they outcompete beneficial plants.

Forbs (flowering plants) provide more invertebrates (bugs) for birds that have high protein needs, including upland birds. They’re also great for pollinators. Eradicate pepperweed, thistle, mustard and radish – they’re not beneficial, and they outcompete beneficial plants.

A mix of grasses and broad-leafed plants/forbs helps provide structure and shade, which can help keep late-season eggs from cooking when inland temperatures get into multiple 100-plus-degree days – when the annuals start to die, the perennials provide more cover.

Encourage native vegetation along the wetland/upland transitions and edges. Native forbs can provide dense, tall cover and help keep invasive pepperweed out. This will reduce time and money spent eradicating undesirables.

Certain farm fields can provide really attractive nesting habitat, particularly cereals (wheat, oats, triticale) and cover crops (vetch, hay, alfalfa, rye grass). If located next to flooded rice (food-rich and safe habitat for broods), this can be a bonanza for nesting ducks. The downside is you can’t count on all the eggs to hatch before harvest or other necessary, but destructive, activities.

It is always best for a nest to hatch naturally and ducklings be raised by the hen, but for situations where this isn’t possible, California Waterfowl has the Egg Salvage Program. We help farmers collect eggs before they’re destroyed and get them to a federally permitted facility that will incubate the eggs and rear the ducklings, then release them into the wild. Click here for more information.

Uplands need vegetation management, just like wetlands. If you grid or spot-spray your undesirables, it will help keep perennial grass stands happy and increase the percentage of desirable plants that provide better nesting cover. Mowing and burning in fall or winter will help set back perennials and remove residual vegetation. It may even help displace predator communities within your uplands, which will improve your nest and duckling success.

Many land managers need to mow roads and levees for valid reasons, so if you must mow, do so early and often to deter ducks from nesting there. Only mow the portion of the levee where you actually need to drive.

SPEAKING OF PREDATORS…

Predator communities vary regionally. Where you may have lots of raccoons, another manager may have a skunk issue. And there are some predators you just can’t do anything about because they are protected.

Remember: Everything has to eat to live! Also keep in mind these animals do not rely on duck nests and ducklings year-round; many of them eat what many landowners consider pests: rats, mice, voles, ground squirrels, moles, crawdads and a variety of insects.

NEST PREDATORS

In California the main culprits are skunks and raccoons, which move throughout the landscape on roads, ditches, sloughs and wetland edges. It’s hard to avoid this when we’re recommending uplands to be located near water, but one thing you can do is try to keep your upland nesting fields away from roads and levees.

What about coyotes? They’re not typically big nest predators. And they may actually help keep out skunks and raccoons. In the Prairies, coyotes are not even in the top three duck nest predators. They’re considered less detrimental to nest production than red foxes (the No. 1 nest predator), and where they co-exist, coyotes kill or displace foxes from their territories, making them more beneficial than not. If you remove the coyotes, chances are you just opened the door for the real nest predators to move in for a meal.

Raccoons: Based off data from raccoons tagged with transmitters, adult raccoons appear to establish territories. They also have personal preferences. Overall, most don’t spend much time in upland fields searching out nests, so if you remove a raccoon that did not exhibit that behavior, then you just opened up his territory to be occupied by another animal that might.

Raccoons: Based off data from raccoons tagged with transmitters, adult raccoons appear to establish territories. They also have personal preferences. Overall, most don’t spend much time in upland fields searching out nests, so if you remove a raccoon that did not exhibit that behavior, then you just opened up his territory to be occupied by another animal that might.

Skunks: It is unclear whether skunks have established territories, but it seems their habitat use among individuals overlaps to a much greater extent than raccoons. Males use roads and levees to a much higher degree and rarely roam uplands, except when pursuing a female. On the other hand, post-breeding females separate from males and mosey around uplands somewhat regularly.

Dens are often associated with a water source. It’s debatable whether they seek out nests, or just take advantage when they happen upon them. Either way, a skunk is too small to consume an entire nest but can return to a previously visited nest to grab another egg or two for a meal.

DUCKLING AND ADULT DUCK PREDATORS

Avian and mammalian predators are the main source of duckling and adult mortality outside of hunting season. Everything likes to eat ducklings: skunks, raccoons, coyotes, otters, mink, birds of prey (hawks and owls), ravens, crows, black-crowned night herons, egrets, fish, bullfrogs and snakes.

Not all avian predators eat the same prey, with some focusing more on small mammals year-round, while others are generalists that prey more heavily on nesting hens and ducklings only when they are available and abundant.

The dominant avian predators are great horned owls, herons and likely red-tailed hawks. Northern harriers, or marsh hawks, likely do not eat many ducklings, but they are important scavengers of dead ducks and cripples during the winter. All birds of prey, herons and egrets are protected.

Surprising to many, snakes are also duckling predators, especially gopher snakes. While they cannot successfully consume eggs from the nest because the eggs are too large, that doesn’t keep them from trying.

Fish and sometimes turtles also pose a threat to ducklings under one week old (think bass and stripers).

Lastly, river otters move in family packs and can corner and consume a brood in no time, and there’s nothing you can do about it: They’re protected.

PREDATOR MANAGEMENT

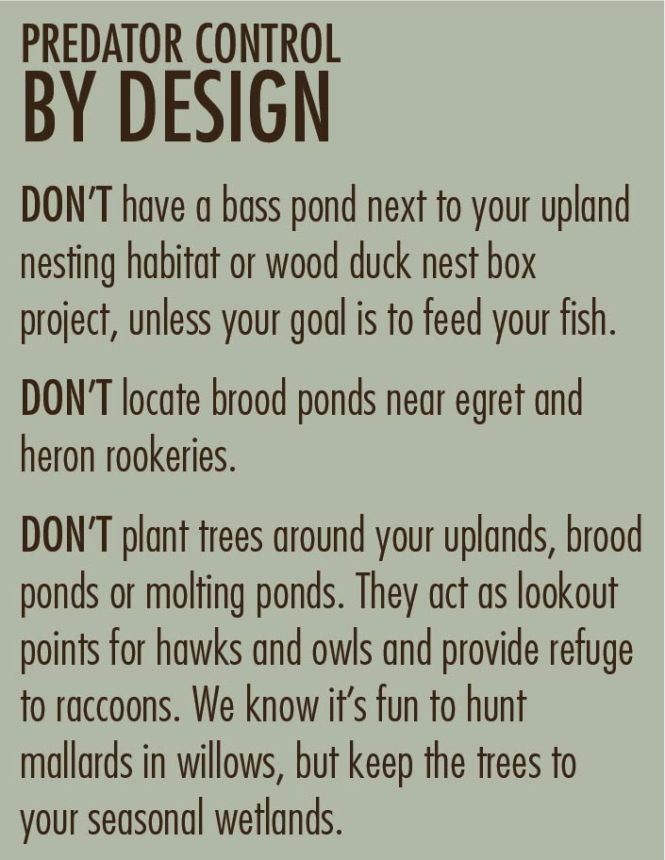

It’s a popular belief that predator management can do wonders to improve nest success. Although this may be true on a small scale, it is not really a viable long-term option, especially on a large scale. This type of management is only really effective on islands where ground nesting birds and introduced predators cohabit and can be completely eradicated. For us in California, it’s more effective (and less time-consuming) in the long run to limit predators with the design of your habitat.

It’s a popular belief that predator management can do wonders to improve nest success. Although this may be true on a small scale, it is not really a viable long-term option, especially on a large scale. This type of management is only really effective on islands where ground nesting birds and introduced predators cohabit and can be completely eradicated. For us in California, it’s more effective (and less time-consuming) in the long run to limit predators with the design of your habitat.

If you increase nest success within a trapped block by controlling predators, you get more ducklings coming off the landscape, but wherever your property ends, there will be plenty of predators on the perimeter. Once a hen leads her brood off the safety of your property, she is providing predators a veritable fluffy duckling buffet.

Remember that increased prey leads to increased predators. So, the longer you maintain predator control, the more likely you’ll be attracting more of the very same predators you are trying get rid of.

That said, managers should take note if they see large predatory fish in their brood ponds. Consider a fishing derby or drain your pond to get rid of the fish.

GIVE DUCKLINGS A PLACE TO GROW: BROOD WATER

Ducklings need water that has food for growth and cover for protection. Forbs are very beneficial because they can increase invertebrate quantity and diversity – important duckling food. Perennial and annual plants (tules, cattails, smartweed, watergrass) can provide more structured habitat for birds to hide in.

Ducklings need water that has food for growth and cover for protection. Forbs are very beneficial because they can increase invertebrate quantity and diversity – important duckling food. Perennial and annual plants (tules, cattails, smartweed, watergrass) can provide more structured habitat for birds to hide in.

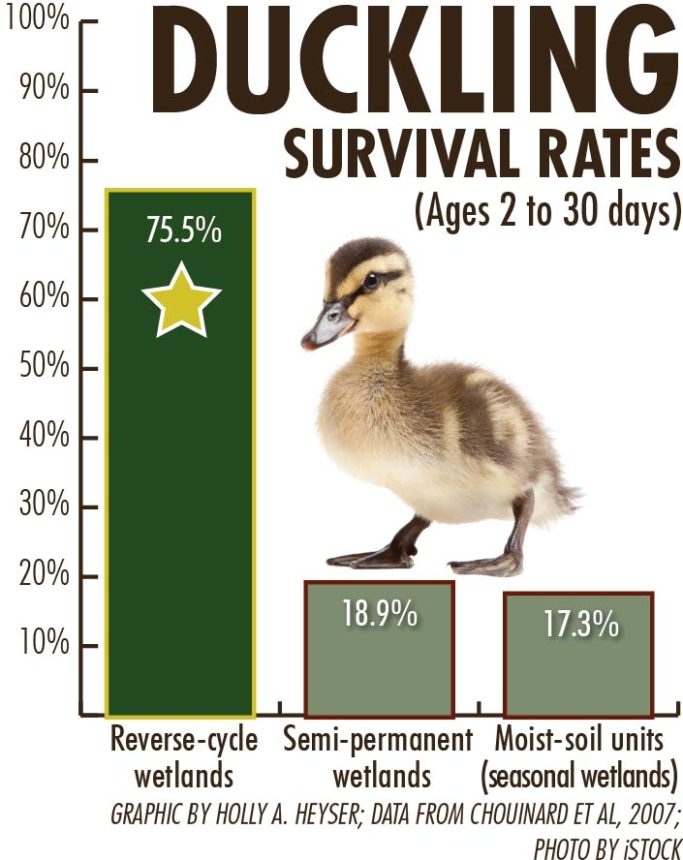

There are two common types of brood water: reverse-cycle wetlands that are flooded in spring and summer, but dry in fall and winter, making them (largely) unhuntable, and semi-permanent wetlands that can rear broods in spring and summer, be drained to allow discing or mowing, then reflooded for hunting.

There are two common types of brood water: reverse-cycle wetlands that are flooded in spring and summer, but dry in fall and winter, making them (largely) unhuntable, and semi-permanent wetlands that can rear broods in spring and summer, be drained to allow discing or mowing, then reflooded for hunting.

Reverse-cycle wetlands are significantly better for broods: Duckling survival can be up to 300% higher, in large part because they are rich in invertebrates (duckling food), and the lack of semi-permanent or permanent water deters predators from calling them home.

If you cannot accommodate a reverse-cycle or semi-permanent wetland, then delay drawdown of managed seasonal wetlands until mid-summer to allow for increased breeding territories.

GLOSSARY

Permanent wetland: Flooded year-round. Not the best brood water due to sparse invertebrate populations and aquatic predators such as bullfrogs and bass, but excellent for molting, and if the water is clear, sago pondweed may grow, and it’s desired by gadwalls, ring-necks, redheads and canvasbacks.

Seasonal wetland: This is what we typically hunt. Ideally, it’s loaded with moist-soil plants that ducks love to eat, but basically, if you’re growing duck food, you ain’t growing ducks. We drain these when the season is over, and they are largely dry by summer, though irrigation in May, June and July may make them somewhat useful to breeding ducks and ducklings. However, as they drain, hens move their broods, which usually leads to duckling mortality.

Semi-permanent wetland: These brood ponds can be flooded in fall and spring, or continuously from fall until at least July 15, but preferably August 1. Then they can be drained and disced to set back vegetation and prep for hunting season. Remaining dry for two to six months a year is ideal for maintaining desirable vegetation. Larger is better, but 4-25 acres makes them manageable.

Reverse-cycle wetland: The opposite of seasonal wetlands, kept dry for most of hunting season and providing the much-needed summer water. This regime promotes the best vegetation and invertebrate populations for broods and discourages predator use.

BROOD POND DESIGN

Incorporate shallow benches with water depths of about 1.5-2 feet, swales with water depths of about 3 feet, and potholes with depths of 2.5-3 feet (potholes must be tied to swales to allow them to drain). Include islands into your wetland design. Varying water depths help safeguard ducklings from being stranded, as the deeper areas will hold water longer. They also encourage different invertebrate communities to flourish at different depths.

Downside: The smaller dimension, shallower water and high summer temperatures contribute to high rates of evaporation and transpiration, which can let vegetation get out of control. That means managers need to check brood ponds weekly to prevent them from drying up and stranding broods, forcing them to walk to another water source. Rice fields are great to have near brood ponds, as they act as surrogate wetlands if your brood pond goes dry. Rice that is at least 30 days old provides cover for ducklings and hens, and high amounts of invertebrates.

Avoid water level fluctuation: Big changes in water levels prompt hens to move their broods to another wetland, which usually leads to duckling mortality. Every time water reaches a new level, it hits mosquito eggs and triggers a new hatch. Keep your wetland water levels at a stable 6-12 inches minimum to avoid this, or you’ll be paying for mosquito abatement. This also promotes the accelerated growth of cattails.

Depending on where you are in the state, you can set your boards at the desired level and keep a slow, constant flow of water. Circulation is key for encouraging invertebrates and plant growth. In the Suisun Marsh, it also helps keep your brood pond from becoming a duckling-unfriendly salt pond.

VEGETATION MANAGEMENT

Swales and potholes help distribute and drain water, reduce aggressive tule and cattail growth, maintain healthy populations of mosquito predators like mosquito fish and dragonfly larvae, and create the open water duck hunters love in the winter. Shallow shelves can grow moist-soil seeds, increasing the value of your breeding wetland for the duck season.

Swales and potholes help distribute and drain water, reduce aggressive tule and cattail growth, maintain healthy populations of mosquito predators like mosquito fish and dragonfly larvae, and create the open water duck hunters love in the winter. Shallow shelves can grow moist-soil seeds, increasing the value of your breeding wetland for the duck season.

Every semi-permanent wetland will need to be drained and usually disced at some point to deal with vegetation, but don’t do this all at one time – it takes away all the habitat at once for an entire season. Doing it piece by piece creates a mosaic of wetland progression within your unit, and then you’ve got a variety of wetland plants that will be attractive to birds year-round.

Use your tools! Mowing, discing and burning are your friends, especially discing. Most hunters hate walking in a disced field, but you can use a finishing disc or rollers to break up big dirt clods and make your walk easier. You can also just leave the area around your blind free from discing if it bothers you that much, so long as vegetation is not an issue.

A WORD ABOUT MOLTING HABITAT

When ducks go through wing molt, they lose all their flight feathers at once, rendering them unable to fly for at least 3-4 weeks. To survive this, they need water with a lot of space, food and cover, and they need to be sure it won’t dry up.

Locally breeding California mallards and gadwalls do something unique among dabblers: They migrate to molt, usually returning to the same site each year. The Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex and the Sacramento Valley (when it has the habitat) are critical molting areas.

Drakes start molting when hens begin incubating nests. Unsuccessful nesting or non-breeding hens molt next, and the last to molt are hens that nested successfully – they usually stay with their ducklings for 30 days, and they can conclude molting as late as Oct. 1.

Adequate molting habitat is one of the scarcest habitats in our state. At the Klamath Basin complex, outbreaks of naturally occurring botulism happen nearly every summer, and it takes a toll on molting birds. Water shortages exacerbate the problem as crowding leads to easier and faster spread of the disease.

Molt survival could be one of the bottlenecks restricting population growth in California, and increasing molting habitat can be difficult because it requires relatively large permanent wetlands. This is why most molt habitat is on public land. There used to be more molting habitat available in the Central Valley, and survival is better when birds choose to stay here to molt. This is where private land managers can combine forces to provide this habitat type.

BREEDING HABITAT PROBLEMS & SOLUTIONS

LOSS OF HUNTING HABITAT

Converting hunting units to ideal breeding habitat may reduce your huntable area, but you can ameliorate that loss by converting sub-par hunting units, marginal habitat and sanctuaries.

If you take a hunting unit that isn’t performing well and turn it into a semi-permanent wetland, you can flood it mid-winter and the new water will attract ducks precisely when the season is at its peak and when most seasonal wetlands are sparse of food. Enjoy some hunts, then keep the water on it through spring and summer to help broods (this mimics what happens when the Central Valley floods). This is as close as it gets to having your cake and eating it too. In addition, you may be able to get some state or federal funding to support this effort.

Marginal habitat such as fields near a road, powerlines or your clubhouse likely don’t hunt well. These could be great candidates for an upland nesting field, a reverse-cycle (dry in winter) or semi-permanent wetland, especially since human disturbance in the spring and summer is minimal compared with during duck season. While it’s not ideal to be near roads, more breeding habitat is better than less.

Converting sanctuary to semi-permanent wetland might seem counterintuitive – don’t the ducks need the food provided by seasonal-wetland sanctuaries? In theory, yes, but sanctuaries tend to get fed out first, so ultimately birds use them really just to rest and loaf. Additionally, by concentrating most of your moist-soil units (i.e. most of the food) in your hunt zone, you encourage waterfowl to visit your hunting area more often, increasing your take opportunity.

MOSQUITO ABATEMENT COSTS

Water in spring and summer is a breeding ground for mosquitoes, which can incur fees and spraying by your local vector control district.

Typically, semi-permanent and permanent wetlands don’t incur these costs, just seasonal wetlands – the ones you hunt. Why? Because you can have mosquito fish in these wetlands, which naturally manages mosquito populations. These wetland types are also great at producing predatory invertebrates, like dragonfly larvae, which eat mosquito larvae. And ducks love to eat those too.

How to avoid mosquito abatement:

• Flood quickly – flood one unit to capacity at a time, then move on to the next one. This will reduce the need for multiple sprayings.

• Keep your water levels stable and circulating.

ENGINEERING AND FUNDING

Like the idea of contributing to the breeding habitat solution, but not sure how to go about it, or how to pay for it?

California Waterfowl has six regional biologists who plan and execute wetland projects on both public and private land. Their training and expertise can help ensure any project is a successful one. If you are interested in working with them, or even just seeking their advice, click here.

POTENTIAL FUNDING SOURCES

FEDERAL GRANTS

NAWCA (North American Wetlands Conservation Act): Funds projects on both public and private lands with a 50-50 cost share. Typically covers major infrastructure needs. Contact CWA NAWCA coordinator Chadd Santerre if you have a property you would like assessed.

NRCS (USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service): Varies by county and what programs your local NRCS office offers. For example, in Northeastern California, they have the Regional Conservation Partnership Program, which pays landowners to flood pastures, creating wet meadows for spring migrants.

STATE GRANTS

Comprehensive Wetland Habitat Program: Includes various ways landowners can get monetary assistance for conservation efforts through the state. (Contact: Brian Olson.)

Presley Program: Funds projects on private land. Provides private landowners with technical assistance and financial incentives to manage wetland habitat. Incentive rates vary depending on the habitat type you chose to provide.

Landowner Incentive Program: Focuses on the Central Valley's three predominant historical habitat types: wetlands, native grasslands and riparian habitat.

Permanent Wetland Easement Program: In cooperation with the Wildlife Conservation Board's Inland Wetland Conservation Program, this program pays willing landowners 50% to 70% of their property's fair market value to purchase the farming and development rights in perpetuity. The landowner retains many rights including trespass rights, the right to hunt and/or operate a hunting club and the ability to pursue other types of undeveloped recreation, such as fishing and hiking.

Wildlife Conservation Board: Works within the California Department Fish and Wildlife. WCB's three main functions are land acquisition, habitat restoration and development of wildlife-oriented public access facilities. WCB projects focus on the Central Valley floor, which extends approximately 400 miles from Red Bluff to Bakersfield and encompasses the following nine basins: Butte, Colusa, Sutter, Yolo, American, Suisun Marsh, Delta, San Joaquin and Tulare.

Inland Wetlands Conservation Program: Offers a range of options to accomplish WCB goals, including acquisitions of land or water for wetlands or wildlife-friendly agriculture, acquisition of conservation easements, restoration of public or private lands, or enhancement of existing degraded habitats. In addition, the program will work toward providing long-term reliable water for wetlands and winter-flooded agricultural lands.

Agricultural Program: The intent of the funding is to assist landowners in developing wildlife-friendly practices on their properties that can be sustained and co-exist with agricultural operations.

Resource Conservation boards: Provide private landowners with technical assistance in permitting, water control and habitat management to ensure the wetland and wildlife values are sustained and enhanced. For example, the Suisun Resource Conservation District holds annual landowner meetings with applicable management info.

OTHER

Bird Return Program: Funded by The Nature Conservancy, this program encourages flooding of rice after the hunting season, which is good for breeding pairs. For more information please email birds@tnc.org or call 916-449-2852.

INFORMATION SOURCES FOR THIS ARTICLE

In addition to numerous interviews with experts at both government and non-government conservation agencies, this article was based on the following studies:

Ackerman, JT, J Kwolek, R Eddings, D Loughman, and J Messerli. 2009. Evaluating upland habitat management at the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area: effects on dab¬bling duck nest density and nest success, year 1 baseline report. Administrative Report, U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Davis, CA and California Waterfowl Association, Sacramento, California, USA.

Ackerman, JT, JM Eadie, SL Oldenburger, GS Yarris, DL Loughman, and RM McLandress. 2006. Age related reproductive success of mallards in California. Fourth North American Duck Symposium, Bismarck, North Dakota, USA.

Ackerman, JT, AL Blackmer, and J. M. Eadie. 2005. Is predation on waterfowl nests density dependent: a test at three spatial scales. Oikos 107: 128-140.

Ackerman, JT 2002. Of mice and mallards: positive indirect effects on coexisting prey on waterfowl nest success. Oikos 99: 469-480.

Amundson, CL and TW Arnold. 2011. The role of predator removal, density-dependence, and environmental factors on mallard duckling survival in North Dakota. The Wildlife Society 75: 1330-1339.

Baldassarre, GA and EG Bolen. 2006. Waterfowl ecology and management. Second Edition, Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida, USA.

Baldassarre, GA. 2014. Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America. Wildlife Management Institute, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Bellrose, FC. 1980. Ducks, geese, and swans of North America. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, USA.

Blank, SC, K Jetter, CM Wick, and JF Williams. 1993. With a ban on burning - incorporating rice straw into soil may become disposal options for growers. California Agriculture 47: 8-12.

Central Valley Joint Venture. 1990. Central Valley Joint Venture Implementation Plan – a component of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Sacramento, California, USA.

Central Valley Joint Venture. 2006. Central Valley Joint Venture Implementation Plan – Conserving Bird Habitat. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Sacramento, California, USA.

Chouinard, MP Jr. and TW Arnold. 2007. Survival and habitat use of mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) broods in the San Joaquin Valley, California. The Auk 124: 1305-1316.

Cowardin, LM, DS Gilmer, and CW Shaiffer. 1985. Mallard recruitment in the agri¬cultural environment of North Dakota. Wildlife Mongraphs 92.

California Waterfowl Association. 2017. Principles of wetland management. California Waterfowl Association, Roseville, California, USA.

De Sobrino, CN, TW Arnold, and CL Feldheim. 2017. Distribution and derivation of dabbling duck harvests in the Pacific Flyway. California Fish and Game 103: 118-137.

Devries, JH, RW Brook, DW Howerter, and MG Anderson. 2008. Effects of spring body condition and age on reproduction in mallards (Anas platyrhynchos). The Auk 125: 618-628.

Feldheim, CL, JT Ackerman, SL Oldenburger, JM Eadie, JP Fleskes, and GS Yarris. 2018. California mallards: a review. California Fish and Game 104: 49-66.

Fleskes, JP and WM Perry. 2005. Change in area of winter-flooded and dry rice in the Northern Central Valley of California determined by satellite imagery. California Fish and Game 91: 207-2015.

Fleskes, JP, JL Yee, GS Yarris, and DL Loughman. 2016. Increased body mass of ducks wintering in California’s Central Valley. The Journal of Wildlife Management 80: 679-690.

Fleskes, JP, DM Mauser, JL Yee, DS Blehert, and GS Yarris. Flightless and post-molt survival and movements of female mallards molting in Klamath Basin. 2010. Waterbirds 33: 208-220.

Fuller, AK, CS Sutherland, JA Royle, and MP Hare. 2016. Estimating population density and connectivity of American mink using spatial capture-recapture. Ecological Applications 26: 112-1135.

Gehrt, SD and S Prange. 2006. Interference competition between coyotes and raccoons: a test of the mesopredator release hypothesis. Behavioral Ecology 18: 204-214.

Heitmeyer, ME. 1987. The prebasic moult and basic plumage of female mallards (Anas platyrhynchos). Canadian Journal of Zoology 65: 2248-2261.

Heitmeyer, ME. 1988. Protein costs of the prebasic molt of female mallards. The Condor 90: 263-266.

Howeter, DW, JJ Rotella, MG Anderson, LM Armstrong, and JH Deveries. 2008. Mallard nest-site selection in an altered environment: predictions and patterns. Israel Journal of Ecology & Evolution 54: 435-457.

Johnson, MA, TC Hintz, and TL Kuck. 1987. Duck nest success and predators in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana: the central flyway study. Great Plain Wildlife Damage Control Workshop

Proceedings 73: 125-133.

Kaminski, MR, GA Baldassarre, JB Davis, and RM Kaminski. 2013. Mallard survival and nesting ecology in the Lower Great Lakes region, New York. Wildlife Society Bulletin 37: 778-786.

Lariviere, S. 1999. Mustela vison. The American Society of Mammalogists 608: 1-9.

Lewis, JC, KL Sallee, RT Golightly Jr., and RM Jurek. 1998. Social and biological aspects of non-native red fox management in California. Proceedings of the 18th Vertebrate Pest Conference 53: 150-155.

Loughman, DL, GS Yarris, and MR McLandress. 1991. An evaluation of waterfowl production in agricultural habitats of the Sacramento Valley. Final report to California Department of Fish & Game. California Waterfowl Association, Sacramento, California, USA.

Loughman, DL and MR McLandress. 1994. Reproductive success and nesting habitats of Northern harriers in California. Final report to California Department of Fish & Game. California Waterfowl Association, Sacramento, California, USA.

Matchett, EL, and JS Sedinger. 2008. A change in waterfowl species composition in the Honey Lake Valley, California. California Fish & Game 94: 44-52.

Matchett, EL, DL Loughman, JA Laughlin, and RD Eddings. 2007. Factors that influence nesting ecology of waterfowl in the Sacramento Valley of California: an evaluation of the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program. Final report to California Department of Fish and Game. California Waterfowl Association. Sacramento, California, USA.

Mauser, DM. 1991. Ecology of Mallard ducklings on Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, California. PhD dissertation. Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon.

Mauser, DM, and RL Jarvis. 1994. Mallard recruitment in northeastern California. Journal of Wildlife Management 58: 565-570.

Mauser, DM, RL Jarvis, and DS Gilmer. 1994. Survival of radio-marked mallard ducklings in Northeastern California. Journal of Wildlife Management 58: 82-87.

McLandress, MR, GS Yarris, AEH Perkins, DP Connelly, and DG Raveling. 1996. Nesting biology of mallards in California. The Journal of Wildlife Management 60: 94-107.

Miller, MR, JD Garr, and PS Coates. 2010. Changes in the status of harvested rice fields in the Sacramento Valley, California: implications for wintering waterfowl.

Munro, RE and CF Kimball. 1982. Population ecology of the mallard: VII. Distribution and derivation of the harvest. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Resource Publica¬tion No. 147. Washington D.C., USA.

Naylor, LW. 2002. Evaluating moist-soil seed production and management in Central Valley wetland to determine needs for waterfowl. M.S. Thesis. University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA.

Oldenburger, SL. 2008. Breeding ecology of mallards in the Central Valley of California. M.S. Thesis. University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA.

Petrik, K, D Fehringer, and A Weverko. 2012.Mapping seasonal managed and semi-permanent wetlands in the Central Valley of California. Final report to Central Valley Joint Venture. Ducks Unlimited, Rancho Cordova, California, USA.

Prange, W and SD Gehrt. 2007. Response of skunks to a simulated increase in coyote activity. Journal of Mammalogy 88: 1040-1049.

Ringelman, KM, JT Ackerman, JM Eadie, and J Kwolek. 2009. Duck nest monitoring at Grizzly Island Wildlife Area: 2009 report. Administrative Report, U. S. Geo¬logical Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Davis, CA and California Waterfowl Association, Sacramento, California, USA.

Rienecker, WC. 1990. Harvest, distribution, and survival of mallards banded in Califor¬nia, 1948-82. California Fish and Game 76: 14-30.

Rienecker, WC, and W Anderson. 1960. A waterfowl nesting study on Tule Lake and Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuges. California Fish and Game 46: 481- 506.

Rogers, CM and MJ Caro. 1998. Song sparrows, top carnivores and nest predation: a test of the mesopredator release hypothesis. Oecologia 116: 227-233.

Rowher, FC. 1992. The evolution of reproductive patterns in waterfowl. In Ecology and management of breeding waterfowl. Batt, BDJ, AD Afton, MG Anderson, CD Ankney, DH Johnson, JA Kadlec, and GL Krapu, editors. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota. USA.

Sacks, BN, HU Wittmer, and MJ Statham. 2010. The native Sacramento Valley Red Fox. Final report to

the California Department of Fish and Game. California State University, Sacramento, California, USA.

Sargeant, AB and PM Arnold. 1984. Predator management for ducks on waterfowl production areas in the Northern Plains. Proceedings of the 11th Vertebrate Pest Conference: 161-167.

Sedinger, JS and RT Alisauskas. 2014. Cross-seasonal effects and the dynamics of waterfowl populations. Wildfowl 4: 277-304.

Skalos, D, and M Weaver. 2018. 2018 California Waterfowl Breeding Population Sur¬vey. California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Sacramento, California, USA.

Wolff, PJ, CA Taylor, EJ Heske, and RL Schooley. 2015. Habitat selection by American mink during summer is related to hotspots of crayfish prey. Wildlife Biology 21: 9-17.

Yarris, GS and DL Loughman. 1990. An evaluation of waterfowl production on set-aside lands in the Sacramento Valley, California. Final report to the California Department of Fish and Game and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. California Waterfowl Association, Sacramento, California, USA.

Yarris, GS, MR McLandress, and AEH Perkins. 1994. Molt migration of post-breeding female mallards from Suisun Marsh, California. Condor 96: 36-45.

Yarris, GS. 1995. Survival and habitat use of mallard ducklings in the rice-growing re¬gion of the Sacramento Valley, California. Final report to California Department of Fish and Game. California Waterfowl Association, Sacramento, California, USA.