Aug 11, 2021

2021-22 Fall Flight Forecast

There may be some great opportunities. But truthfully, there’s all kinds of bad news this year.

By Caroline Brady, Waterfowl Programs Supervisor

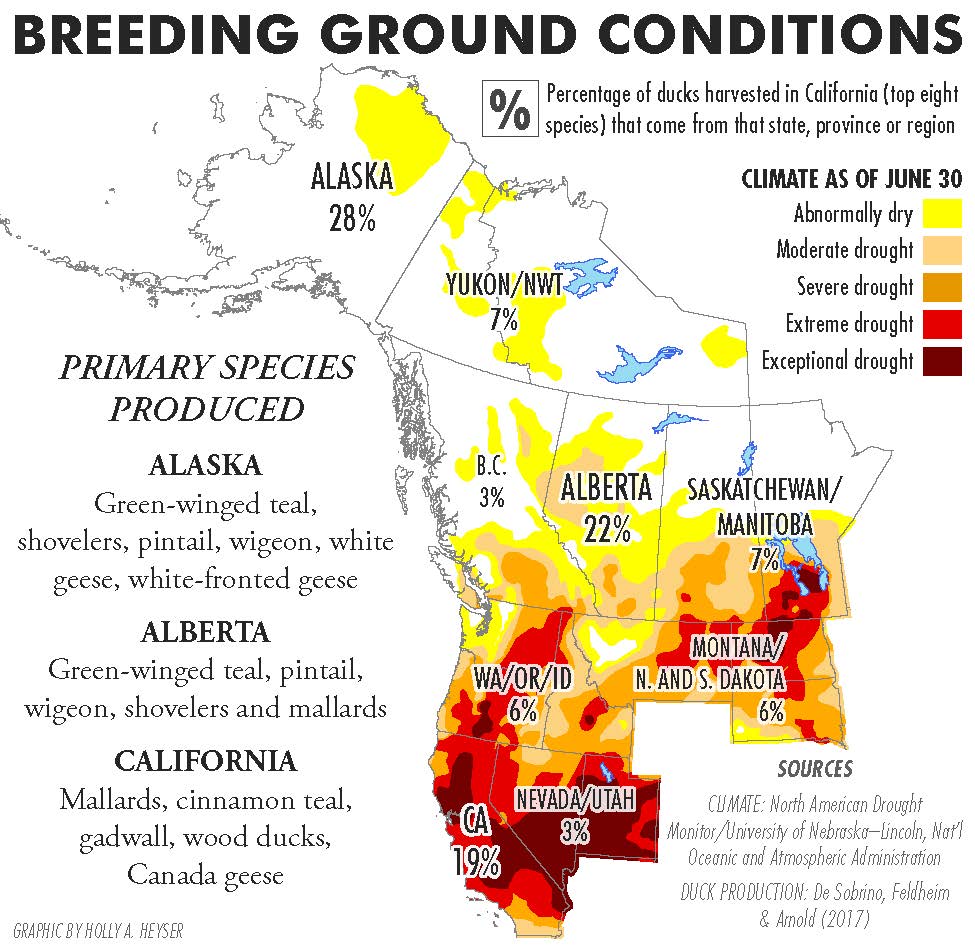

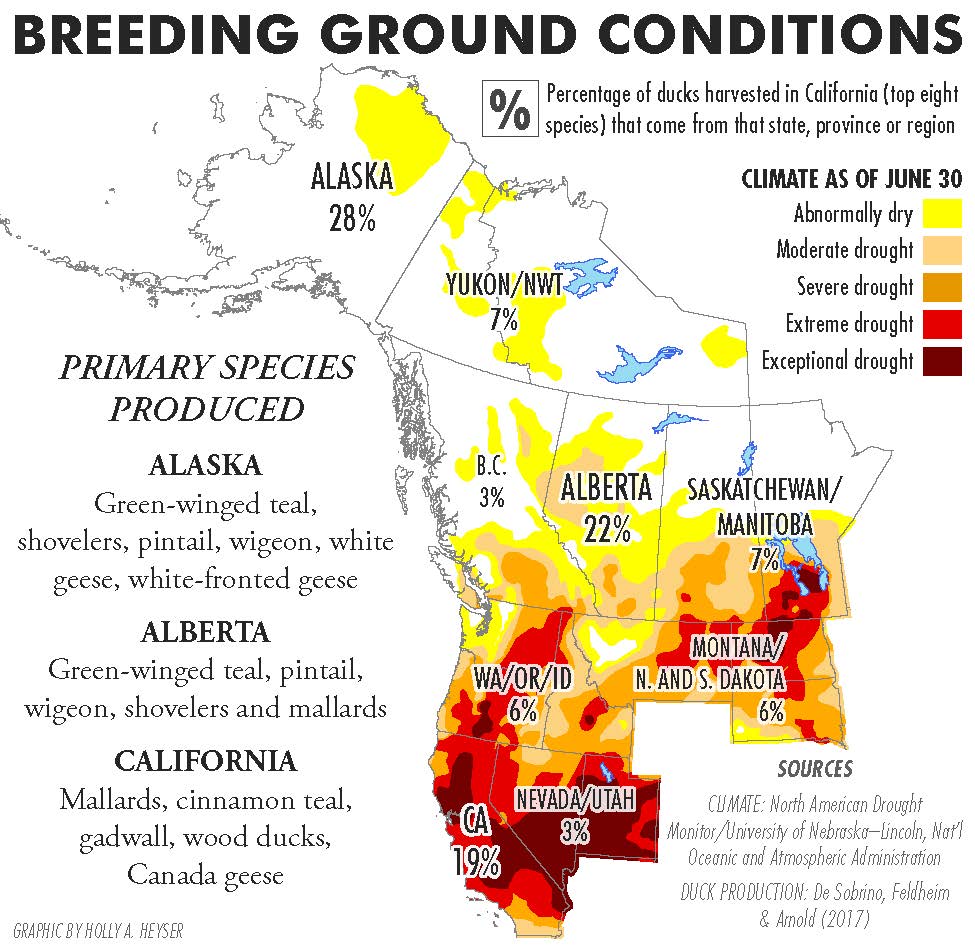

Drought conditions in breeding grounds critical to waterfowl that winter in California. Click to view full-size.

Where to begin…

We’re in the second year of drought. This is not helping our local mallard, gadwall and cinnamon teal populations, which have largely been in decline for the last decade.

But beyond local production woes, these are extraordinary times my friends. The drought is so widespread that two major fall staging areas that Pacific Flyway birds depend on – the Klamath Basin and the Great Salt Lake – are at all-time lows.

This means you can expect a whole lot of waterfowl to arrive early in the Central Valley. They will be searching for freshly flooded wetlands, rice and corn fields. And they will find far less water than usual.

Which means you will find far less than usual, come hunting season. Across the board you can expect a varying degree of reduced hunter quotas and delayed and staggered flood-ups on public land, and a lot of unflooded rice fields this winter.

One silver lining: Efficient use of recycled tertiary water by managers in SoCal means the San Jacinto Wildlife Area will be fully flooded for the opener. The Wister unit of the Imperial Valley Wildlife Area will be in decent condition, too.

Of course, last time we were in drought, if you had a place to hunt, the hunting was often exceptional. And you’ll see below that some duck-producing regions important to California had good conditions this year. So, there’s a good chance that any time you do spend afield this season should be productive.

Read on for all the insight we can offer so you can guess how this season might look for you, depending on where, how and what you hunt.

WHAT’S AFFECTING PRODUCTION

THE CALIFORNIA SCENE

Unfortunately, duck and Canada goose production through most of the state appears to have been poor.

This is bad because 60% of the mallard and 49% of the gadwall we harvest come from California. Between this and substantial numbers of our wood duck and cinnamon teal also being California-hatched, nearly one-fifth of our most-harvested ducks come from within the state.

Even in “normal” water years, quality breeding habitat (both natural and agricultural) has become scarcer. Ongoing drought has reduced summer nesting and wetland acres further.

Ducks that nested probably experienced reduced success due to poor habitat conditions and increased predation, which we saw in our field work this year. Less habitat means less ground to cover when you’re a predator looking for a meal.

Biologists banding family groups of Canada geese in Northeastern California this summer encountered many more adults than goslings, suggesting production was low.

Some positives

In Northeastern California, duck production appeared to be fair on areas that had summer water: Tule Lake NWR, Modoc NWR and the Ash Creek Wildlife Area.

In the Sacramento Valley, ag-based nesting duck programs offered by CWA and the California Rice Commission remained popular. While about one-fourth of rice acres were fallowed this year due to water curtailments (can’t plant) and water transfers (choose to sell water instead of plant), about 390,000 acres were planted, which isn’t bad. All of that rice served as a safe haven for ducklings – flooded and therefore rich in food and cover to hide from avian predators.

The North Delta likely hosted more breeding ducks than usual this year simply because it had water. For example, some of our Delayed Wheat Harvest Incentive Program’s most prolific fields bordered the Stone Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, and the Hastings Island Hunting Preserve in the Delta was off the hook with breeding mallards.

A mallard with her brood at the Hastings Island Hunting Perserve. PHOTO BY MARK BOYD

In the Grasslands, several landowners participating in the Presley Program actively pumped groundwater to maintain the summer wetlands they had into July. Our mallard banding crew saw nesting effort pay off for some, though production appeared limited.

The molting problem

Production isn’t the only factor limiting the local ducks we’ll see in our skies this fall; there’s a high likelihood we’re losing a large proportion of our breeding stock right now because molting habitat is in short supply.

Ducks shed their wing feathers and become flightless for 30 to 60 days in late summer, so they need a safe place to eat and live during that vulnerable time. Some of our local birds molt in the Central Valley’s limited summer wetland acreage, but many migrate to Southern Oregon-Northeastern California, which is usually rich in rivers, lakes, reservoirs and public lands.

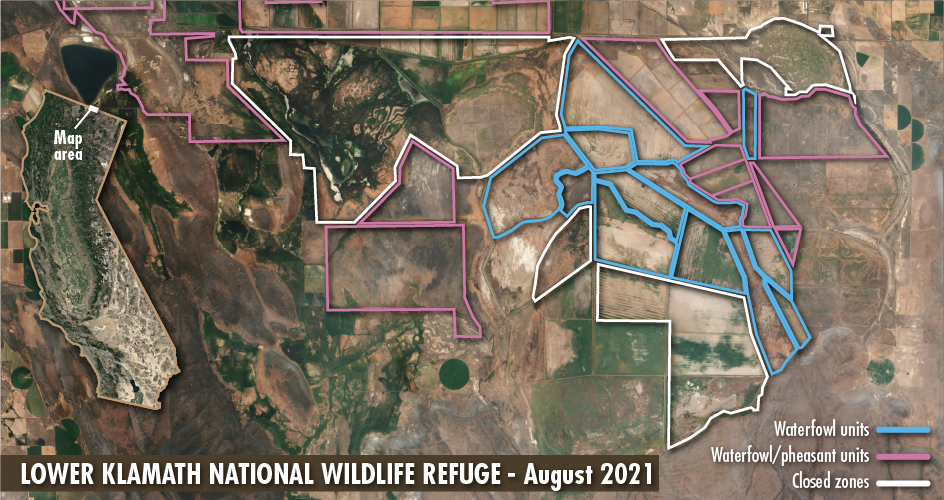

Larger wetland areas, like the Klamath Basin NWR Complex, often meet the bulk of molting ducks’ needs, particularly mallards. But wetland habitat has withered there over the past decade, and this year the Klamath refuges are in even worse shape than last year, when a catastrophic botulism outbreak killed over 60,000 ducks, geese and shorebirds.

Lower Klamath's last water - Sheepy Lake - was drying up as of early August.

Other wetland complexes, like Summer Lake NWR in Oregon and smaller California public lands, have picked up the slack. The problem is most of those are also dry or very low this year, though Summer Lake has a good number of flooded units.

OTHER SOURCES OF OUR DUCKS AND GEESE

The biggest sources of ducks we harvest each year are Alaska (28%) and Alberta (22%). No other single U.S. state or Canadian province comes close, though other Canadian provinces combined produce about one-fourth of the ducks on our straps. So how were these areas looking?

Alaska

Alaska was the best situated to produce ducks this year, with fair to good habitat conditions throughout much of the state. Green-wings, shovelers, pintail, and wigeon – which also come in large numbers from the Alberta, Yukon and the Northwest Territories – should be plentiful.

More than a third of our pintail come from Alaska, so good conditions there could be a boon for our sprig.

Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia boreal forest

The Canadian boreal forest stretches from Yukon and northern British Columbia to Newfoundland and Labrador. Although it is characterized by its forests, it also has many natural treeless areas and thousands of lakes, rivers and wetlands.

When the prairies are dry, some species like pintail will take refuge in the boreal to nest. Some species commonly nest there, like ring-necked duck, scoter, scaup, green-winged teal and wigeon. And good news! Conditions there were considerably wetter than on the Canadian and U.S. prairies.

However, the extent to which those conditions persisted is largely unknown as population surveys were not flown. The only discouraging information coming out of the boreal is that the region has been experiencing hot, dry weather since June and fire risk is high.

U.S. and Canadian prairies

The U.S. and Canadian prairies were in poor condition this year due to drought. Reduced production there will impact hunting far more in the Central and Mississippi flyways than in California, although nearly half of our pintail come from prairie Canada (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba). In dry years like this, many pintail will attempt nesting in the boreal forest, but this typically equates to lower production.

On the bright side, it’s actually good for wetlands to dry out periodically, so when the prairie drought ends, the region’s wetlands will likely be much more productive.

Throughout the U.S. and Canadian prairies, Alberta was in the best shape, which is good given that it is our most important source of ducks coming out of Canada. Spring conditions were good in west-central and northern Alberta but deteriorated toward the southeast. In mid-June, summer heat began drying out wetlands, so late-nesting species like gadwall and scaup had less quality habitat available to them. But a good number of broods were observed.

Arctic goose colonies

We heard from biologists in the field that nesting colonies of white-fronts on Alaska’s North Slope, and brant and cacklers on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, had fair to good production.

Canadian arctic breeding geese – mainly white geese – were left mostly undisturbed by researchers again this year. This means we have no population survey data and very little anecdotal information about production.

A few researchers were able to get out this spring, and the consensus is that nesting appeared to start about two weeks late. Generally, late nesting is synonymous with poor production. And we don’t have any word yet from Wrangel Island, which sent one million snow geese our way last year.

WHAT’S AFFECTING WINTERING

(AND HUNTING) HABITAT

The same drought that’s suppressing duck production is also affecting our wintering habitat, in two key ways:

WATER

Water years 2020 and 2021 are the second driest two-year period on record to date, behind 1976 and 1977. The second year of this exceptional drought brought with it reduced water allocations throughout the state. In March, Oroville water users were cut 50%, Shasta users 25% and Tehama-Colusa Canal users received nothing.

This affects both food production (agricultural and wetland) and flooding for fall and winter, mitigated somewhat by groundwater pumping.

Just about every public area irrigated some portion of their sanctuary and hunt area to grow food. Although it may have been less than in a normal water year, they made sincere efforts. And almost no area expects to flood as much land this winter as it normally would.

The number of acres of rice forecasted to be flooded after harvest, as of this writing, is expected to be about 80,000 acres valley wide (it’s normally 270,000 acres). This means unless you’ve got access to groundwater, your rice blind is likely to be flooded late, if at all.

Keep in mind this is a dynamic situation – we will likely endure further cuts. And a large portion of what little water we have in storage will likely be prioritized for fall salmon runs and flushed down river to control salinity in the Delta. We won’t truly know the pickle we’re in until we’re in it.

TIMING

Fall staging habitat is crucial to migratory birds because it provides an area to rest and fuel up during long-distance travel – a big rest stop on the long highway from breeding areas to wintering areas.

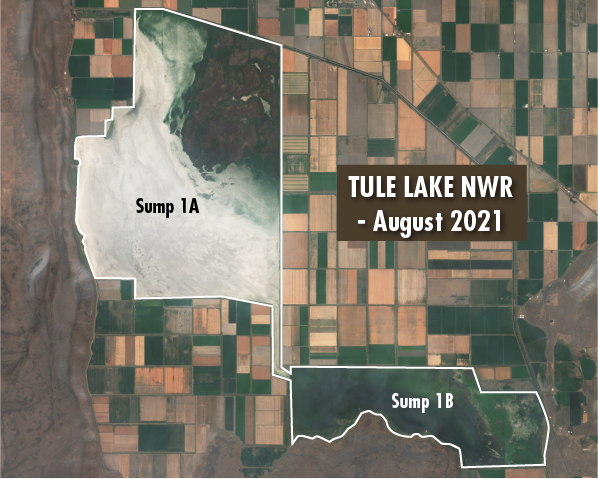

This year, staging grounds are in dire condition. Combined, the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake NWRs will have perhaps 2,600 acres flooded compared with the normal 40,000-acre wetland footprint.

Sump 1A was drained deliberately this summer to reduce the area where botulism can occur, but the move is also expected to promote the growth of waterfowl food plants in the future. Sump 1B has also lost water.

The Great Salt Lake has hit an all-time low, and its wetland habitats have been reduced from 425,000 acres to 110,000 acres.

Staging habitat in the Klamath Basin plays a very important role in how duck season kicks off. Migratory waterfowl arrive in the Basin in late summer/early fall, and while birds rest and get fat in Northeastern, the Central Valley plays catch-up with its fall habitat, flooding wetlands and harvested rice fields. As harsher weather sets in and food resources thin out up north, birds begin to migrate south and slowly trickle into the Central Valley throughout the season.

This year, with little to no fall staging habitat available for the millions of fall migrants, the Central Valley should expect to see an early arrival of hungry birds starting in late August, when we will be struggling to flood up sufficient amounts of habitat. In effect, it’s like having your huge family show up a couple months early for Thanksgiving dinner – imagine the strain that would put on your household resources.

WHAT ALL THIS MEANS FOR YOUR DUCK SEASON

Many of the areas that produce most of our mallards were in poor condition, so it feels safe to predict that it is not going to be a good mallard year. On the flip side, green-wings, pintail, shovelers, ringnecks and wigeon should be abundant this fall. But weather and overall habitat availability throughout the flyway will dictate bird movements and ultimately how frequently you shoulder your gun.

If you’re lucky enough to have water at your rice blind, you could have a great year because the birds will have fewer places to go. Same goes for public and private lands hunting – if there’s water, it should be lights-out.

Many duck hunters ask us if we should reduce mallard limits to lower the harvest when things are this bad. The truth is that when mallard populations are low, we harvest fewer mallards (California’s mallard harvest rate has flatlined over the last 25 years) without laying a hand on the limits. Harvest isn’t what’s holding them back: Habitat is the issue. To learn more about what affects California's mallard populations, click here.