Aug 28, 2020

This dead mallard shows why Klamath matters to the entire state

If you'd like to understand why water supply problems in the Klamath Basin are a problem for ALL California ducks, look no further than this hen, or rather what's left of her.

If you'd like to understand why water supply problems in the Klamath Basin are a problem for ALL California ducks, look no further than this hen, or rather what's left of her.

Hers is one of more than 20,000 bird carcasses found at the Klamath Basin refuges this summer as the worst botulism outbreak in memory rages. The disease is fueled by high temperatures that activate botulism found naturally in the soil, and greatly exacerbated by the dearth of water at the refuges.

Donate to help save Lower Klamath

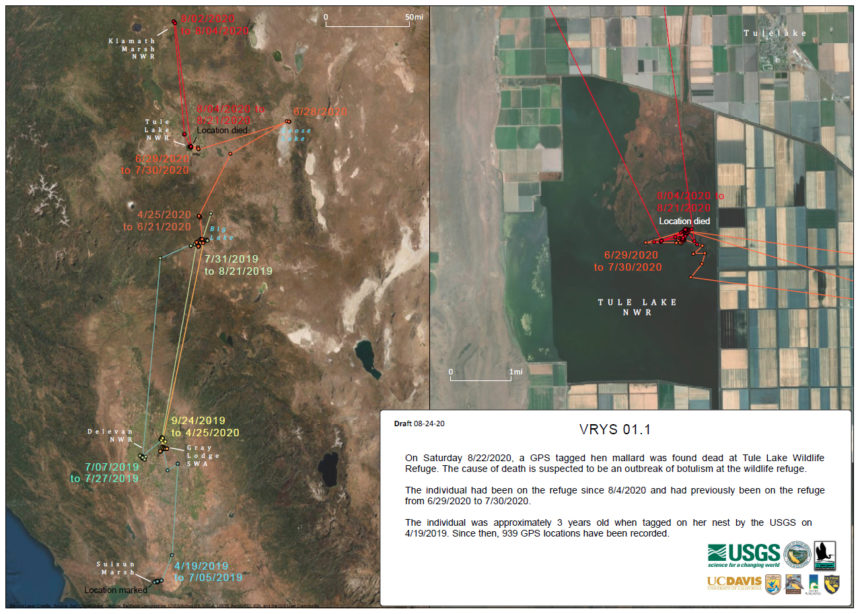

But the fact that this duck was wearing a U.S.G.S. GPS transmitter gives us a lot of insight into how her travels led her to this place:

Last year, she nested in Suisun; spent summer mostly in the Sacramento Valley; headed to the Fall River Mills area to molt. Molting is perilous because ducks lose their flight feathers for 30 to 60 days - they need big water that's safe from predators, and there just aren't a lot of options in the state.

She headed back down to the Valley for the entire fall, winter and spring, then headed back to the Fall River Mills area this spring, possibly to nest. In late June, she headed north to the Klamath Basin as she was preparing to molt.

The hen's travels. Click on the map to see full-sized (PDF).

In the old days, she would have found Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge full of water, and the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge would've had as many as eight units flooded. Conditions like that would make the basin a good place to molt – lots of permanent water, lots of cover to hide in and lots of food to eat. That's why many ducks that winter and breed in other parts of the state head to the Basin in late summer.

Lower Klamath, though, has been cut out of the water supplies it historically used, largely because water has been either held in Upper Klamath Lake or sent down the Klamath River in an attempt to help three species of endangered fish. The diversions have not helped the fish, but they have turned the Lower Klamath refuge into a desert for much of the year. This year it is especially bad because on top of the man-made drought, there is a natural drought. And this year, the Tule Lake refuge needed to drain one large unit to stimulate waterfowl food production, so there was less water than usual there, too.

So this hen arrived at Tule Lake near the end of June and spent a month there. She spent a few days in early August exploring the Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, then headed back down to Tule Lake on Aug. 4 to settle in for the molt. Unfortunately, with high temperatures hitting the basin early this summer, Sump 1A had already become a seething pit of botulinum toxin. Our biologists found what was left of her this week.

California's mallard breeding population is already in poor shape, but having a shortage of water in a key molting area is fueling this year's botulism outbreak, which is translating directly into substantial losses to the mallard population in particular. Unfortunately, this is also when the earliest migrators – pintail – are arriving in the Basin, so biologists have begun finding them among the sick and dying too.

Because this water crisis is tied to the Endangered Species Act, it has proved difficult to solve. But California Waterfowl is fighting hard to save the refuge, with the help of key conservation allies and Basin farmers, who have shared water generously when they were able to. Our key goals are to secure high-priority water rights for the refuge and to secure an agreement for the equitable distribution of water in the Basin, and we have created a special task force to achieve these goals.

To learn more about the crisis, please click here.

If you would like to donate to support our efforts to save Klamath, please click here.