Sep 28, 2018

We're putting solar collars on specks. Here's why.

CWA Waterfowl Biologist Jason Coslovich holds a freshly collared white-fronted goose, aka specklebelly. PHOTO BY WAYNE TILCOCK

BY WAYNE TILCOCK

Have you ever wondered whether growing goose populations might be crowding out and taking food from dabbling duck populations in California in the winter?

If so, you're not alone, and California Waterfowl is assisting a research project that will help answer this question.

In partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey, the California Dept of Water Resources, UC Davis, Ducks Unlimited, California Department of Fish and Wildlife and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, CWA staff have been at the forefront of efforts to capture and attach GPS collars to greater white-fronted geese – specklebellies - caught during our banding operations in the Central Valley. This is part of a larger goose study that includes collaring snow and Ross’s geese at their northern breeding grounds and here in the Central Valley.

The solar-powered collars, which weigh 38 grams, use the Global Positioning System to store a record of the birds’ locations and travel patterns. They can also monitor speed, temperature and even magnetic field strength to give researchers a full plate of information to observe.

Much like sending text messages, the collars will then transmit that data to researchers over GSM cellular networks when the birds are in range of towers.

GSM, short for Global System for Mobile communications, is the most common international cellular standard. That is important in this study since staff from the Canadian Wildlife Service and Russia’s Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources began collaring geese for the study this summer. Their work will help determine what percentage of summer arctic geese typically winter in California’s Central Valley.

These efforts began in February as USGS captured and collared white geese and a small number of white-fronted geese in the Central Valley, tracking their journey back to the breeding grounds.

Waterfowl Biologist Jason Coslovich and Waterfowl Technician Jaime Oskowski take measurements of white-fronted geese captured, banded and collared for research. PHOTO BY WAYNE TILCOCK

Knowing the birds’ travel habits while wintering in California can help us better understand if the geese are in areas that put them in competition for food, habitat and other resources with dabbling ducks.

Of special concern are local dabblers that breed in the Suisun Marsh, the largest contiguous brackish marsh on the West Coast of North America. Those ducks will also winter in the Central Valley and may be susceptible to food competition with expanding goose populations.

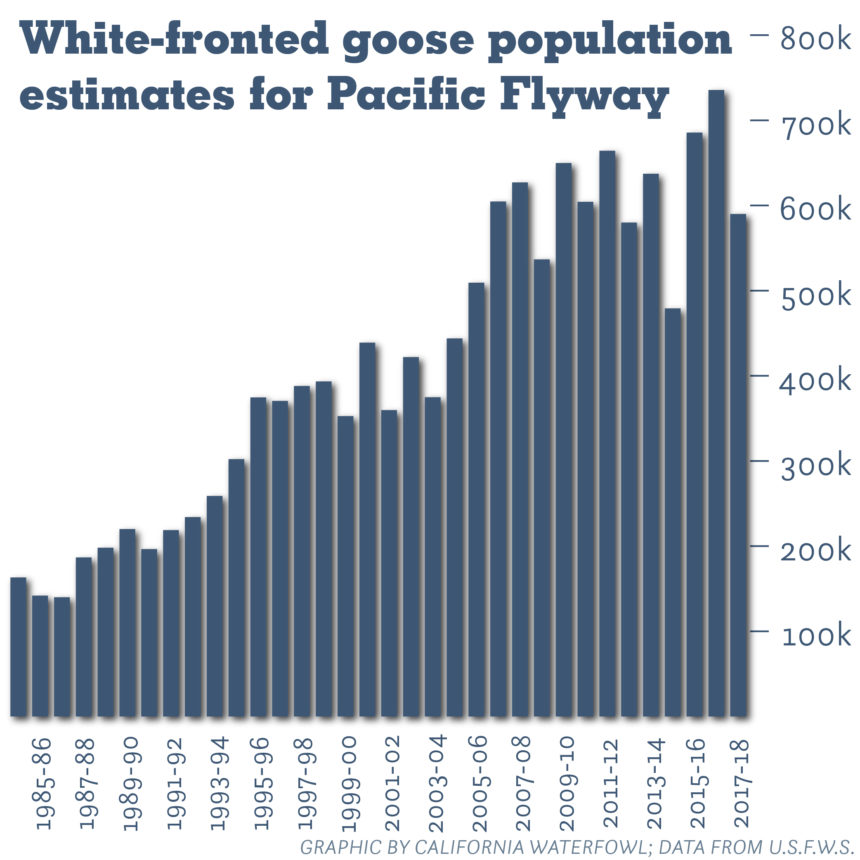

The population of greater white-fronted geese wintering in the Pacific Flyway has tripled from an average of around 200,000 at the beginning of the 1990s to more than 600,000 at its peak from the last three survey years. Lesser snow and Ross’s goose populations are already three times the objective set by the Central Valley Joint Venture, a migratory bird conservation coalition of 21 state and federal agencies, private conservation organizations and one corporation.

Source (see pages 68-69)

Geese will feed in both dry and flooded crop fields. If early-arriving geese feed heavily in dry fields before flooding, they can reduce the amount of food available to dabblers once water is on those fields.

In instances where dabblers and geese share habitat, the higher density of birds could also potentially lead to an increase in disease transmission.

Over the last week, CWA biologists have captured and collared white-fronts at three locations. “We are trying to spread them around to attempt to capture birds from different breeding area sources,” said CWA Waterfowl Biologist Brian Huber. “So far we have placed collars on 15 geese and we have seven more collars to deploy.”

Once the movement and habitat use data is collected and combined with diet studies conducted by other project partners, public and private habitat managers - including CWA - will be able to develop plans that can adjust to increasing goose populations while also working to support dabbling duck populations.

What happens if you shoot one of these geese? Don't worry, you're not in trouble. Read more about what to do here.

California Waterfowl's banding crew L-R: Technicians Natalie O'Connor and Jaime Oskowski, and waterfowl biologists Jason Coslovich and Brian Huber. PHOTO BY WAYNE TILCOCK