Jun 10, 2020

An unusual search mission, powered by CWA volunteers

California Waterfowl volunteers do a lot of amazing things, but sometimes the stuff we ask them to do is just downright weird – and boy do we love them for helping us out.

California Waterfowl volunteers do a lot of amazing things, but sometimes the stuff we ask them to do is just downright weird – and boy do we love them for helping us out.

Case in point: Waterfowl Programs Supervisor Caroline Brady was monitoring the movements of GPS-collared geese recently and noticed that there were two specks near McArthur that had stopped moving and were likely dead – one that had been collared by CWA, and another that had been collared by the U.S. Geological Survey. This happens, so it wasn't the end of the world, but researchers like to get the high-tech collars back because they cost $1,300 a pop.

The good news was that both GPS transmitters were in places where they were getting sun, so, being solar-powered, they were still sending location data. Finding them wasn’t going to be too hard. Well, maybe for one of them – more on that later.

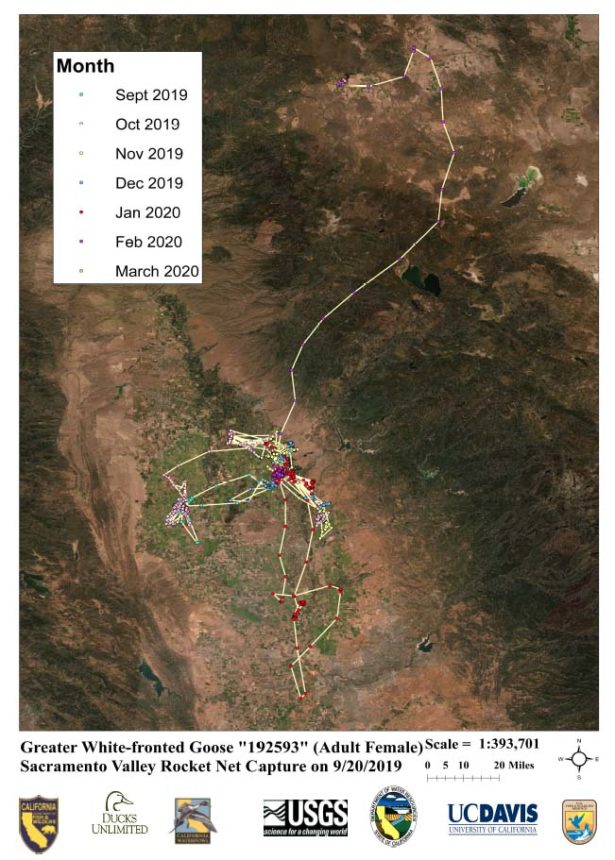

The first collar – number 192593 - was on a mature female goose that was captured by the Department of Fish and Wildlife on September 20, 2019, in a banding operation at the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge Complex. DFW was targeting pintail, but there were specks in the area too, and it was U.S. Geological Survey Waterfowl Research Crew Leader Andrea Mott's chance to recruit more avian agents of research.

That goose spent all last fall and winter toodling around the Sacramento Valley, and she managed to evade hunters' shotguns for the entire regular waterfowl season – she didn't even have to resort to hiding out in the Sacramento Valley Special Management Area during the speck closure!

Starting in February, 192593 made her way toward the northeastern corner of the state, finding some nice farm fields to hang out near McArthur in late February and March. And then something happened around March 11, just after the end of the late goose season in the Northeastern Zone: The collar stopped moving. That bird was dead.

(Story continues below photo.)

So CWA contacted member Vince Decoito – a longtime friend of CWA Hunting and Education Programs Supervisor Jeff Smith – and asked him to see if he could go get it.

“It was pretty straightforward,” he said. “You get the coordinates and it leads you right to it.” He grabbed his two boys and his dog, they took a boat ride to the property, made a beeline to the coordinates and there it was. No dead goose, no feathers, no nothing – just a collar sitting in the grass, with nothing for company but some cows and the occasional deer.

Mack (age 1½) and Hank (age 3½) Decoito with Sage and the goose GPS transmitter collar they found

The cool part is that his boys – Mack, 1½, and Hank, 3½, got to be involved in an important mission at the intersection of science and nature. If the bird’s carcass had been there, they would’ve gotten to keep the aluminum leg band, but sadly, that was not the case. However, Mott is sending them a poster of all the places that goose went while she was collared, which is a pretty cool keepsake.

“I like when kids get involved with stuff because they’re so freakin’ excited,” Mott said.

OK, one collar down. The other story is a little more unusual.

On February 15 this year, CWA’s banding crew did some rocket netting, also on the Sac Refuge Complex and put collar number 193425 on an adult male speck. That one also ended up in the McArthur area this spring, where his collar stopped moving on May 6. Then, two weeks later, something funny happened: It started moving again.

“I got to looking at the details on the website we use to track the collars and I thought, ‘Wow this is kind of weird,’” Mott said. It started moving in a very un-goose like way, moving pretty fast, but never changing elevation. A clear pattern emerged: He was going to work in multiple locations every day, and then going home to the same house every night.

Mott pieced it together: Someone found the collar and set it in his truck, someplace where it was getting enough light for the solar unit to keep charging the batteries – probably on the dash.

She knows it’s creepy to have that level of data. “I promise I’m not trying to be a creep,” Mott said. “I just care about geese.”

For this rescue mission, CWA enlisted a former employee: Rick Maher, who was CWA’s senior regional biologist for the northeastern region for 10 years. He’s now a semi-retired farmer in the area.

Maher looked at the coordinates and recognized that the daytime locations were all on land owned or leased by a particular farmer. He got in touch with the farm foreman and explained the situation.

“Sure enough the next day someone said, ‘Yeah, I’ve got this sitting on my dash.’” Mott had called it!

The collar had been sitting on a levee with a few feathers around it. The guy thought it was some sort of electrical apparatus that belonged in a panel, so he hung onto it. He never noticed that text on the collar that asked anyone who finds it to contact USGS to arrange its return.

There are some GPS transmitters that can never be recovered, Mott said – sometimes birds fly to remote areas where there is no cellular signal, so USGS stops getting data, and the birds never come back into range.

But most hunters are really good about returning the transmitters. In return, they get a non-working transmitter and a map of the bird’s travels as keepsakes.

Recovering transmitters like these, though, requires some help.

“What’s awesome is CWA is so involved and you have so many contacts with everyone,” she said. “That’s how we get most of them back.”