May 28, 2019

The duck-club loving mouse

by KATIE SMITH

For many hunters, there’s probably no better place to be on a crisp winter morning than in a duck blind—hunkered down among the tules under a delicate blanket of fog as the first golden-pink rays of the waking sun ignite frozen breath and warm ruddy cheeks.

That is, until they find they are sharing their sanctuary with a tiny, fuzzy interloper.

But while mice may seem like unwelcome freeloaders at duck clubs, many hunters might be surprised at how closely intertwined native rodents are with waterfowl. This is especially true for those who hunt in the San Francisco Estuary, which is the only place on earth where a very special rodent, the salt marsh harvest mouse, is found.

Over 90% of historical tidal wetlands in the San Francisco Estuary have been lost, primarily to filling for agriculture, industry and urban development. A special subset of these wetlands were diked in the early 1900s and have been managed for waterfowl since. These are largely concentrated in the Suisun Marsh, where over 150 privately owned and anaged duck clubs and a handful of public lands now preserve, maintain and enhance these historical wetlands. That’s about 60,000 acres of wetland habitat—over 10% of all remaining non-agricultural wetlands in California—that have been safeguarded from development for over a century.

But it hasn’t been easy for these dedicated hunters to remain the stewards of the land for all this time. Regulatory hurdles such as water quality standards and concerns over endangered species have complicated wetland management in the Suisun Marsh, and hunters have come under fire for maintaining wetlands behind levees during a time when many entities are seeking to perform as much tidal restoration as possible in anticipation of sea level rise.

One serious challenge has been recovery of the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse. The salt marsh harvest mouse is an amazing wetland specialist—it can climb nimbly in tules, it can swim swiftly and easily, and it can eat salty foods and drink water even saltier than seawater. But one thing it can’t do is fight the loss of habitat.

The mouse was put on the Endangered Species List in the 1970s, and because it was historically found primarily in tidal marshes dominated by pickleweed, it was predicted that waterfowl management—which doesn’t prioritize expansive tidal wetlands or the growth of pickleweed—would cause the species to go locally extinct in areas where waterfowl management was common. This assessment was not totally off base at the time, when research on the species was just getting started.

But the hunters who spend immense amounts of time caring for and recreating on these lands knew that they were protecting great habitat for wildlife, not just for ducks. Soon, a curious group of California Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists (my mentors) began to suspect the same thing, and instead of putting live-traps for salt marsh harvest mice in the tidal wetlands like they were supposed to, they decided to see if wetlands managed for waterfowl really were bad for mice. They weren’t. My mentors caught lots of mice in lots of managed wetlands, and not just in the Suisun Marsh, but throughout the San Francisco Estuary. And this is where the story really begins.

Armed with this knowledge, these biologists spread the word, and soon others throughout the Estuary were finding salt marsh harvest mice in many different types of wetlands. Despite this, managed wetlands were still considered poorer habitat for the species than tidal wetlands. So the mouse biologists went to the drawing board and designed a series of studies to determine just how duck clubs compared with tidal wetlands in terms of habitat value for the mouse. During this time, a waterfowl study in the Suisun Marsh found that rodent abundance was positively correlated with waterfowl nest survival. The author speculated that this association was due to rodents buffering predation pressure. This study further indicated that the relationship between mice and ducks was more complicated than anyone imagined.

Radio collars were fitted to the mice to track movements. The transmitters weigh about as much as a Tic Tac.

For their first study, the biologists live trapped salt marsh harvest mice in different wetland types within Suisun Marsh and found that densities were actually higher in managed wetlands, and that more mice were captured in mixed wetland vegetation than in areas where pickleweed was dominant. At this point, I joined the team, and for my master’s thesis project, we put tiny radio collars on mice to see how they behave during high-tide periods in tidal and managed wetlands. And when I say the collars are tiny, I mean tiny. Each transmitter was about the size and weight of a Tic Tac! For a whirlwind summer, we spent many chilly nights slogging through the marsh following the beeps that led the way to places where mice were hiding from rising waters and hungry predators. We found that movement and habitat use were similar in tidal and managed wetlands.

![]()

These initial studies all seemed to point to the possibility that salt marsh harvest mice do not perceive major differences between tidal and managed wetlands. But we didn’t have the right kind of data to really compare them scientifically. So, for my PhD dissertation project, we went back to the drawing board. The challenge at this point was to be able to collect data to statistically test our strengthening belief that well-managed wetlands are just as good as tidal wetlands for salt marsh harvest mice.

One concern was that since waterfowl managers encouraged the growth of plant species that ducks like to eat, not necessarily the plants everyone believed mice like to eat, that mice wouldn’t have enough food on managed wetlands. Another concern was whether mice could get everything they needed to survive in the same amount of space in managed wetlands as in tidal wetlands, or whether they had to run around like crazy all night in managed wetlands to get enough to eat, find mates and find shelter. These and other underlying concerns fed worries that managed wetlands just couldn’t support as many mice as tidal wetlands.

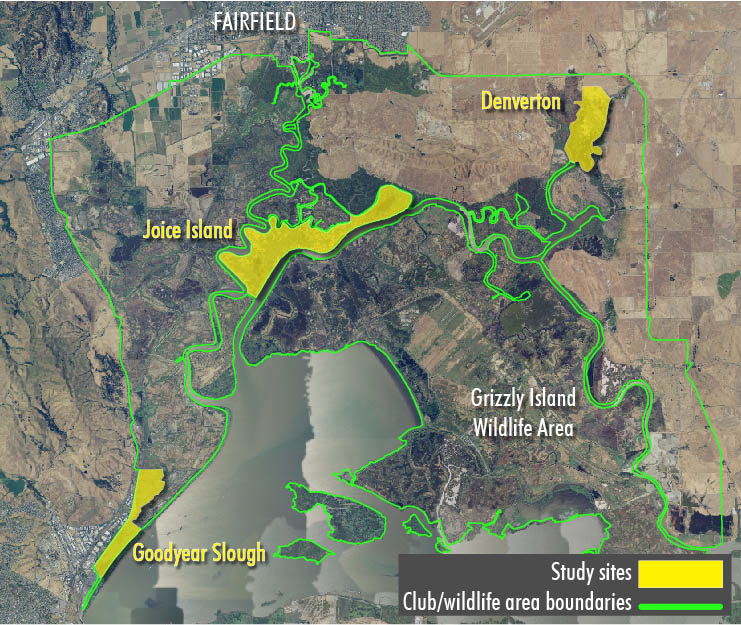

To address these questions, we needed to have data from salt marsh harvest mice in tidal and managed wetlands. So we reached out to wetland managers at California Department of Fish and Wildlife and California Waterfowl to identify sites where tidal wetlands existed near wetlands managed for waterfowl. In the end we chose two areas managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife—the Joice Island and Goodyear Slough units of the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area—and CWA’s Denverton property.

The backbone of the study was monthly live trapping, where we opened small metal box-traps provisioned with yummy seeds and a fluffy cotton bed at sunset and checked and closed them at sunrise. We trapped, marked, and measured mice for three nights per month. To test the value of waterfowl foods for the salt marsh harvest mouse, we performed a diet preference study where we offered them lots of different types of plants once per season, and recorded what they chose to eat. Finally, to learn how the mice use tidal and managed-wetland habitat, we performed another radio-telemetry study, this time during all seasons.

At the end of five years, we had a lot of data that all indicated our belief was correct: Managed wetlands are good for salt marsh harvest mice. Our radio-telemetry data revealed that the mice explored every corner of both tidal and managed wetlands, and foraged and nested in many different types of plants. Some individuals even moved regularly between wetland types. Not surprisingly, considering our movement data, we found that mice ate a lot of different plants, and four of their top five favorites were plants grown for ducks: rabbitsfoot grass, fat hen, watergrass and alkali bulrush! Pickleweed, their presumed favorite, came in third. Finally, our live trapping data showed that survival and population estimates did not differ between tidal and managed wetlands. And while reproductive output did differ by wetland type, the effects were really just differing seasonal shifts.

All of this research over the past decade has transformed our understanding of the salt marsh harvest mouse. This species, which has been managed as a strict habitat specialist for so long, is actually flexible in its habitat use and diet. More importantly, all of this data smashes the assumption that waterfowl management is harmful to the mouse. On the contrary, waterfowl management in the Suisun Marsh provides a lot of high-quality habitat and food for the mice, and has ensured that this huge swath of habitat has been protected and cared for lovingly for over a century. And don’t forget, duck nest survival was higher in the Suisun Marsh when there were lots of mice around, so while waterfowl management is supporting native rodents, the mice are doing their part to bolster waterfowl populations as well!

The salt marsh harvest mouse is endangered, and faces a lot of continuing and emerging threats in the future such as habitat loss, climate change and sea level rise. It has nowhere else to go, and depends on us to thoughtfully protect and manage our remaining wetlands. You can’t have healthy ducks if you don’t have a healthy ecosystem, and though they might be out of sight and out of mind, the salt marsh harvest mouse and other rodents are important parts of waterfowl ecosystems.

So the next time you find yourself sharing a blind with a furry friend, take a moment to appreciate how your support of hunting and land stewardship helps protect endangered species and habitats. And don’t forget that even a tiny mouse can contribute to the health of the habitats that you love to hunt.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Katie Smith is a post-doctoral researcher at the UC Davis Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology and a wildlife biologist with WRA Inc.

The author with a salt marsh harvest mouse.