Aug 27, 2019

Population survey: Mallards need more than water to rebound

PHOTO BY WAYNE TILCOCK

(Originally printed in the Fall 2019 issue of California Waterfowl Magazine)

article by CAROLINE BRADY, WATERFOWL PROGRAMS SUPERVISOR

graphics by HOLLY A. HEYSER, EDITOR

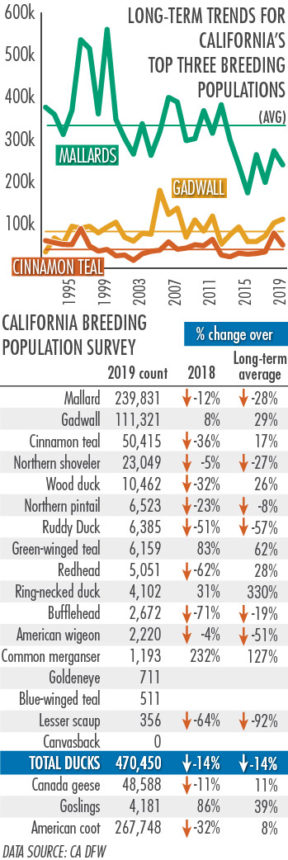

The news from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife this summer was both discouraging and confusing: California’s breeding population of all ducks was down 14% this year, and mallards were down 12% – 28% below their long-term average.

The news from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife this summer was both discouraging and confusing: California’s breeding population of all ducks was down 14% this year, and mallards were down 12% – 28% below their long-term average.

It was discouraging because we had a wet winter and spring, which we expect to translate to good production, and confusing because lots of folks were seeing more mallard broods than usual in their wetlands.

WHY IT MATTERS: 60-70% of mallards harvested in California hatched in California. Our harvest generally tracks with our breeding population.

We can’t tell you exactly what the news means for your hunting this fall. The survey is a sample of California’s breeding population, not a measure of how well those pairs will produce young birds. Mallards are up 2% in the just-released continental breeding population survey, but they’re down 7% in Alberta, which is the second largest source of mallards harvested in California. And of course, we can’t predict the weather.

However, we can tell you about breeding habitat conditions in California – including troubling trends feeding into the mallard decline – and in other parts of the continent.

But first, listen California, I know you all love your greenheads, but spice it up a little, would you? There’s more to duck hunting than mallards. The diversity of waterfowl species that can be harvested here is insane, and diversity is the spice of life.

FAQ: Click here to check out answers to questions about California's breeding population survey.

TROUBLING TREND FOR MALLARDS

In historic California, prior to settlers taming Western rivers and agriculture expanding throughout the state, the most abundant duck species here were likely gadwall, cinnamon teal and redhead, not mallard. But mallards have the flexibility to adapt to a human-altered landscape, and they have expanded their range with the development and growth of agriculture, becoming the most abundant duck in North America.

But all ag is not created equal for mallards, and the ag that has helped them thrive here for decades has been changing.

Duck breeding habitat requires uplands with vegetative cover where hens can make their nests reasonably close to water (less than one mile is ideal) with lots of cover and food. While California has great wintering habitat for ducks, we fall short on natural breeding habitat.

LEARN MORE about California's mallards and what California Waterfowl is doing to help them - click here.

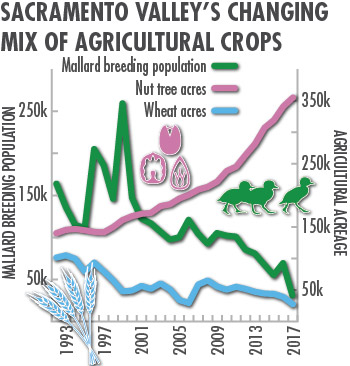

The Sacramento Valley – historically a powerhouse for mallard production but now plummeting – grows some waterfowl-friendly crops, including wheat, oats, barley, triticale and alfalfa. Winter wheat is among the most attractive to nesting ducks. Wheat fields are seeded in the fall and grow throughout the winter. By nesting time, a lush stand of winter wheat near a planted rice field looks like a great nesting location with brood-rearing habitat just a scootch away. Several studies have found ducks may even favor winter wheat over natural uplands when they’re available, and winter wheat in rice country can produce far higher mallard nest densities and nest survival than anything in the Prairie Pothole Region.

But it’s not a perfect substitute: Depending on the year, harvest begins anywhere between mid-May and early June, often before the majority of ducklings can hatch and get out of the field. This results in complete loss of the nest, and sometimes the hen if she doesn’t flush away from the harvester in time.

California Waterfowl has an Egg Salvage Program that works with farmers to salvage eggs before or during harvest, rears the ducklings and releases them into the wild. Does this ease the wildlife-human conflict? Yes. Does it make a dent in mallard population trends in California? No. This is why we are also developing an incentive program to pay farmers to delay wheat harvest so nests can hatch naturally in the field – we hope to launch for testing next spring.

But here’s the thing: Imperfect as wheat is, it at least gives mallards a chance to lay eggs, hatch broods and get them to water. The problem is that in the Sacramento Valley, wheat and other waterfowl-friendly ag such as cereal grains, row crops and pasture are rapidly being replaced with nut orchards, which have as much value to waterfowl as pavement (which is also on the rise with urban development).

Between 1992 and 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, nut tree acreage in the Sacramento Valley increased 154%, driven by nut prices more than doubling. Wheat acreage plummeted 73%. The Sac Valley mallard breeding population declined 81% over the same period, though this year it is 70% below the 1992 population.

Between 1992 and 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, nut tree acreage in the Sacramento Valley increased 154%, driven by nut prices more than doubling. Wheat acreage plummeted 73%. The Sac Valley mallard breeding population declined 81% over the same period, though this year it is 70% below the 1992 population.

There is no clear path to changing farmers’ crop choices on a scale that would impact breeding population trends. Our best bet at this point is to work with farmers to maximize the value of existing wildlife-friendly crops on the landscape.

SAVE THE WHEAT DUCKLINGS! CWA is seeking funding for a pilot project to compensate wheat growers for delaying their harvest until July 15. CWA biologists will measure duck use and production from these fields, as well as farmer satisfaction, to gauge success of the program. If it’s successful, we’ll use these results to leverage additional grants to expand the program’s acreage and impact. Want to help? Click here to donate.

BREEDING GROUND CONDITIONS AND CONTINENTAL SURVEY RESULTS

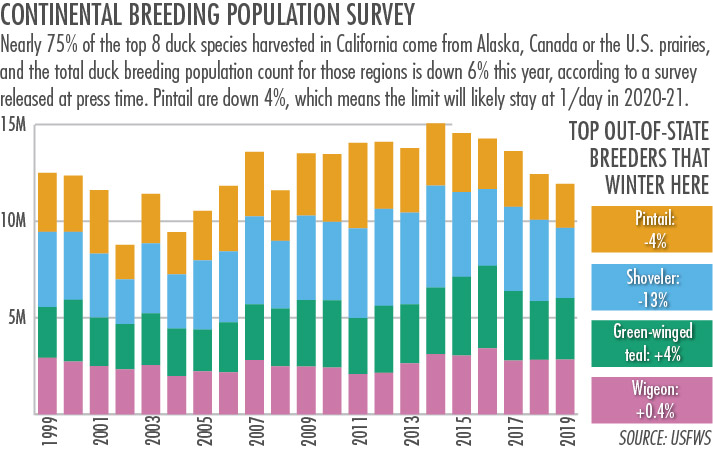

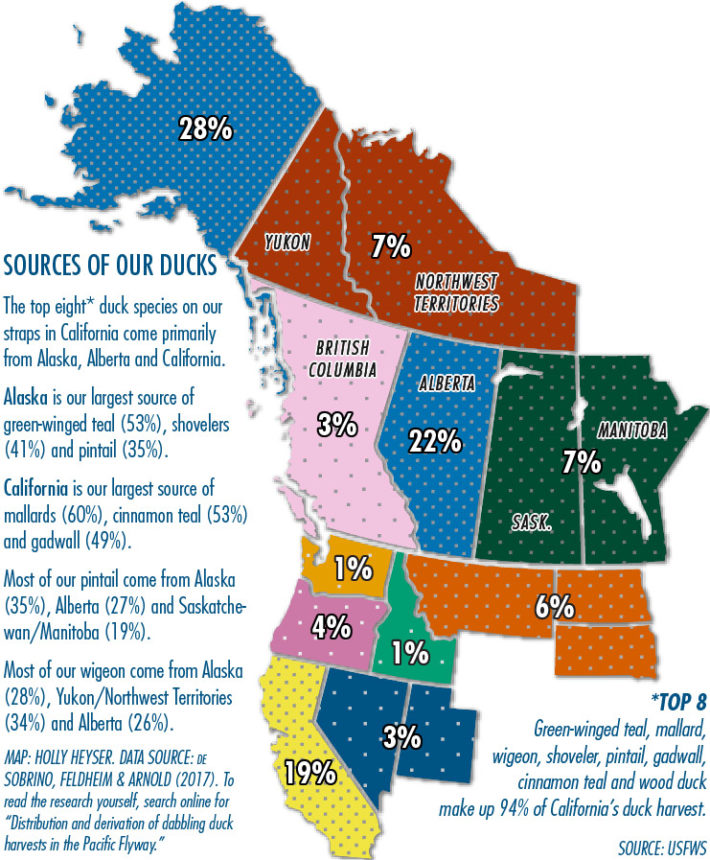

Nearly 70% of the top eight duck species we harvest in California come from three places: Alaska, Alberta and California. Here’s a look at what we know about key sources this year.

CALIFORNIA

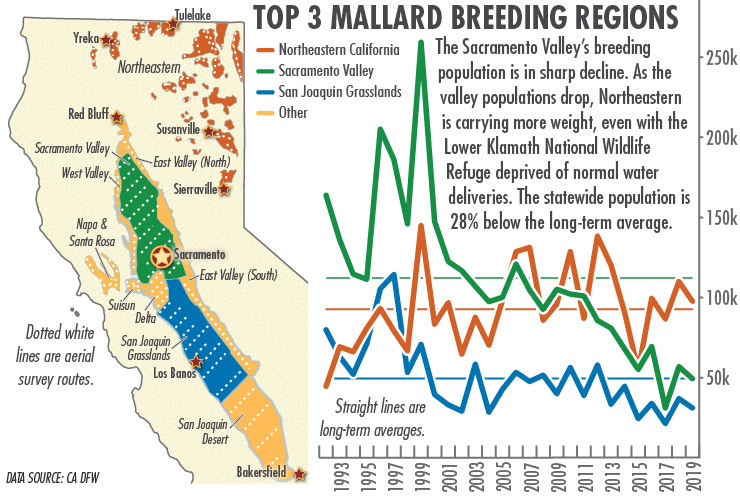

Since the state survey began in 1992, the top three breeding regions in California have hosted 70-82% of all breeding mallards, gadwalls and cinnamons: Sacramento Valley, Northeastern California and the San Joaquin Grasslands.

Since the state survey began in 1992, the top three breeding regions in California have hosted 70-82% of all breeding mallards, gadwalls and cinnamons: Sacramento Valley, Northeastern California and the San Joaquin Grasslands.

SACRAMENTO VALLEY

The Sacramento Valley used to be the state’s mallard factory, but the majority of our breeding mallards appear to be shifting north. Gadwalls, on the other hand, are doing just fine in the Valley: Their population is 27% above the long-term average.

We discussed the Valley’s crop trends, but not the weather: Most rice got planted in time (albeit late) despite the untimely spring rains. The downpours we got in mid- to late May both helped and hurt nesting birds. The rains came right about when hatching peaks, and nests that did not hatch prior to those storm systems risked getting flooded out, especially if they were in bypasses. Ducklings that did hatch before the rains were vulnerable to the elements because they can’t thermoregulate yet. The rain, however, did help keep summer water in wetlands and green up vegetation for species that nest later, like gadwalls, as well as mallards on their second nests.

SAN JOAQUIN GRASSLANDS (AND SUISUN/NAPA-SONOMA)

The San Joaquin Grasslands have remained fairly stable, supporting 11- 20% of our total breeding mallards. The Grasslands have great uplands, but water varies year to year based on precipitation. In that way, it’s similar to the Prairies: When there’s water, there are plenty of ducks. When there isn’t, the ducks aren’t around. It’s a boom-bust system.

Breeding mallard pairs in the Suisun Marsh, Napa-Sonoma, and San Joaquin Grasslands were down from 2018 (-4%, -12%, -16% respectively) but despite that, habitat and wetland conditions were fantastic this summer. The winter precipitation and late May rains set the stage for tremendous production potential. CWA summer banding crews noticed the improved wetland habitat in the Grasslands, and the Suisun Marsh USGS banding crew may break banding records this year.

NORTHEASTERN

Northeastern has always been second to the Sacramento Valley when it comes to mallard production, but not anymore. Over the last 10 years, Northeastern has supported on average 37% of California’s breeding mallards, while the Sac Valley averaged 25%. In 2019, Northeastern hosted a whopping 41% of our state’s mallards; the Sacramento Valley, 21%.

But Northeastern is more than just mallards. These are high desert montane wetland systems, so naturally, “mountain mallards” – or gadwalls – flourish here. More than 70% of our breeding gadwalls were observed in this area, and their numbers in Northeastern are nearly 50% above the long-term average. The iconic cinnamon teal – which draws out-of-state duck hunters from far and wide – was heavily concentrated in Northeastern – 75% of the state’s entire breeding population. Their numbers in the region are nearly 80% above the long-term average.

Pochards like redheads and ringnecks were seen in big numbers in some areas, and production for these birds looks very good. Canada geese may be down compared with last year, but production was very good – expect to see more honkers this fall.

The Northeastern landscape is dominated by refuges, natural habitat and complementary agriculture, creating a large area of upland nesting habitat amidst a variety of wetland types (natural and managed wetlands, cattle ponds, reservoirs). Above-average rains and snowpack in the region helped to maintain unmanaged wetlands in the region, as well as provide adequate water resources for wetland management. The Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, which has suffered greatly from dwindling water supplies from the Klamath Water Project, had more water within its boundaries this spring and summer than it has in a long time, thanks to strong late winter and spring precipitation. However, as of this writing, the refuge is receiving little maintenance water to support important wetland habitat.

ALASKA

ALASKA

It is this massive state, not the prairies, that provides us with most of our other duck species. It is our single largest source of pintail, green-winged teal and shovelers.

Alaska had some great potential for production this year as well, but it was unseasonably warm and drier this year. Ice breakup on many rivers was the earliest on record this spring, the state hit 90 degrees for the first time on record, and many parts of the state experienced summer fires.

The continental breeding population survey reported a 23% drop in the duck breeding population in Alaska, including drops of 7% in green-winged teal, 34% in pintail and 12% in shovelers.

READ MORE:

—Pintail breeding population down - click here.

—What CWA is doing about pintail limits - click here.

CANADA: ALBERTA, SASKATCHEWAN & MANITOBA

These three provinces used to be the source of most of our pintails, but that is shifting to Alaska. Still, Alberta provides 27% of our pintails, while Saskatchewan and Manitoba deliver 19%. Nesting pintails have been having a tough go at it here for some time. This is believed to be due to conflicts while nesting in spring wheat stubble. It’s similar to our mallard woes in winter wheat, only pintail nests are destroyed during field prep for planting, not harvest.

The Canadian prairies were much drier this spring, and it showed in the continental survey: The total duck breeding population there was down 22% from last year (12% from long-term average). The pintail population was down 50% from 2018 (83% from the long-term average) in prairie Canada. It was up 74 percent in the very soggy U.S. prairies this spring, but that’s not enough to move the needle on the regulations – pintail limits will likely remain at one a day for 2020-21.

But don’t fret about conditions in Canada: The record number of ducks counted over the last five years in the prairies has largely been due to great wetland conditions, but when wetlands hold water year after year, they can become less productive. Wetland drying is a necessary stage of wetland succession; it makes them more productive in the following wet years.

Alberta is also a big source of our wintering green-wings and wigeon, which favor nesting in the boreal forest north of the prairies, so the ag-wildlife conflict is more or less absent here. However, in the past 10 to 15 years, the boreal has experienced forest fragmentation from industrial development: hydropower, mining, and oil/natural gas exploration and pumping. Habitat fragmentation is rarely advantageous to wildlife.