Aug 24, 2018

Duckling treks 5 miles to find water

Ducklings have very specific habitat needs when they're flightless.

BY WAYNE TILCOCK, ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Ducks are no strangers to long distance travel, sometimes flying thousands of miles to reach the perfect feeding or nesting grounds.

For most mallards, that life of travel doesn’t start until they can get air under their wings, when they're about two months old. Until then, their mothers have to keep them safe.

Hens nest on dry ground, but they try to choose locations a short distance from suitable water where they can quickly take their hatchlings. The water needs to be deep enough to keep out land-based predators like coyotes but shallow enough to allow plant cover that can provide protection from aerial attacks.

But for one duckling at the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area in the Suisun Marsh, the water its mother thought was going to be available dried up, leading the hen to embark with her brood on a perilous 5-mile trek over land and up Nurse Slough to find that right patch of water. Its journey ended at California Waterfowl’s Denverton property with just one tough duckling surviving.

How do we know this? Technology.

It was late May at Grizzly Island when Andrew Greenawalt, a lead biological science technician with U.S. Geological Survey, first encountered the brood of nine hatchlings. The lot were all web tagged (metal tags clipped onto the webbing of one foot, because the ducklings are too small to band), while two were selected at random to be fitted with small radio transmitters, too.

Greenawalt was at Grizzly Island in the third year of a study examining duckling survival, brood ecology, habitat use and movements in relation to wetland habitats and salinity at the wildlife area and the private lands surrounding it.

In the previous two years of the study, the farthest Greenawalt had tracked ducklings moving was about 2 miles from their nesting site, making this duckling’s expedition more than twice as far as previously recorded in the marsh.

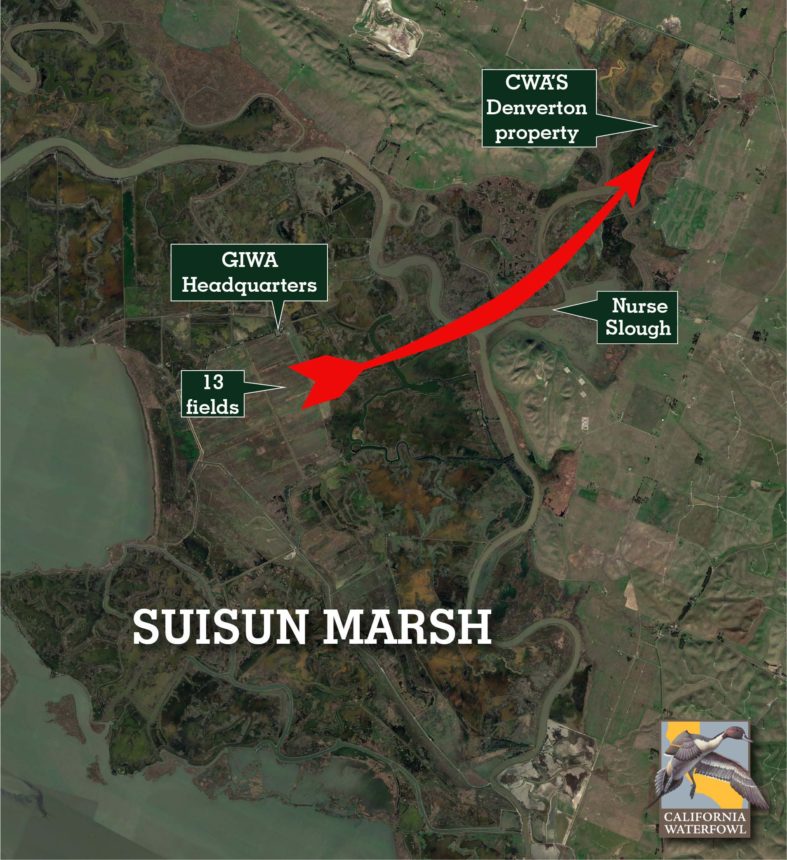

“There have been scientific studies before showing that mallards can travel anywhere up to 2 to 5 miles on land to get to suitable water brooding habitat for their brood,” Greenawalt said. “So that’s something we were working on at Grizzly Island Wildlife Area. It went all the way from one of the 13 fields (upland fields just southeast of the refuge headquarters) to Denverton in about a two-and-a-half-week span.”

This map shows the general route the duckling took as it trekked across the marsh to reach Denverton.

Greenawalt noticed that, despite having a good year for breeding with decent amounts of rain and upland cover, there was a lot less water for ducklings this summer in the wildlife area and at surrounding duck clubs. “It could just be a weird year where private lands and the state wildlife area had to drain to do work,” he added. “But it could also be due to (fresh) water availability.”

Meanwhile, CWA regional biologist Robert Eddings noticed an abundance of ducklings on CWA’s Denverton property at the northeast corner of the marsh.

The ponds there needed to be drained for vegetation management and general maintenance to prepare for hunting season. Traditional water management for seasonal wetlands involves flooding up in September or October through duck season then drying between April and June.

“I was getting ready to drain it, but I was driving around and saw about 40 or 50 little fluffball ducklings and decided that didn’t make sense to me,” Eddings said. So he held the water on the property.

“Managing a property for waterfowl, I’m not about to leave them stranded. And a lot more of them are going to die if they have to leave the property than if they stay here," he said.

“No one is obligated, but if you’re managing a property for waterfowl, a common resource that we’re all trying to protect, we need to be aware of changing conditions from year to year within your region and pay attention to what you’re doing compared with what’s going on around you. For obvious reasons, land managers tend to focus on the upcoming hunting season and wintering waterfowl needs, but we need to remember that locally breeding waterfowl have needs too.”

With Denverton providing habitat that wasn’t available elsewhere nearby, it wasn’t long before Eddings got a call from Greenawalt about a little duckling that had marched a long way just to get to those ponds.

Using a VHF radio receiver to triangulate the ducklings’ position since their hatching on May 26, Greenawalt had been tracking the daily movement of the transmitter-fitted ducklings. In early June, this brood began moving east and north from the nest site, across other private duck clubs in search of good water.

The VHF radio transmitter used to track this duckling on the Suisun Marsh.

About 3 miles into their journey the other duckling that was carrying a transmitter disappeared on another duck club, likely falling victim to an aerial predator.

By the time they reached Denverton on June 13, after more than 5 miles of traveling, Greenawalt tracked down the duckling and found that it was the hen’s only survivor of the brood. The pair stayed there until at least June 26, when the transmitter slipped off (which it’s designed to do), and Greenawalt believes the duckling was healthy enough to survive until it was old enough to fly.

For Eddings, hearing that made him feel good about his decision to hold water and delay earthwork.

“The longer you keep water in the summer, the more cattails, tule, phragmites and other vegetation you get in the swales and ditches, stuff we’re trying to keep out for water flow and drainage,” Eddings added. “That’s more maintenance that needs to be done. So now we have to do more work in a shorter window.

“But in the end, we did it for the ducks.”

Thanks to Eddings’s careful water management, this lucky duck was able find the suitable habitat needed to help it along on to its life as a long-distance traveler, as did many others.

“That it went that far looking for a place to go and made it, and obviously the fact that we were providing the habitat that they chose in the end, we’re excited to know.”

This is the mallard duckling that Andrew Greenawalt, a lead biological technician with the U.S. Geological Survey, tracked to CWA's Denverton property. The duckling trekked 5 miles from its nest site at Grizzly Island Wildlife Area to find the good water that California Waterfowl's staff made available for an abundance of ducklings this summer.