Aug 20, 2019

Can wetlands survive the new groundwater law?

(Originally printed in the Fall 2019 issue of California Waterfowl Magazine.)

by JEFFREY A. VOLBERG, DIRECTOR OF WATER LAW AND POLICY

by JEFFREY A. VOLBERG, DIRECTOR OF WATER LAW AND POLICY

California has a new groundwater law that poses challenges to water users who rely on wells and pumps. Each water user has to ask, “Will I have enough water to go around?” and, “Can I afford to continue to pump water?” This will be particularly difficult for duck club owners, who usually do not have an income stream from their properties to absorb the costs.

In 2014, the California Legislature passed a new Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). SGMA requires that each groundwater basin in the state form a Groundwater Sustainability Agency and formulate a Groundwater Sustainability Plan. The idea is to prevent overdrafting of groundwater that has depleted aquifers, caused land subsidence, reduced water storage and reduced surface water supplies in certain basins.

Before SGMA, California’s water rights law allowed unlimited pumping of water under any piece of real property. In cases where too much pumping caused groundwater levels to drop and wells to dry up, landowners could be subject to “correlative rights” under which they are allowed a proportionate share of groundwater along with neighboring landowners. Landowners are restricted to “reasonable use” of water, the definition of which can vary according to circumstances.

In some areas of California where overdrafting caused real problems among groundwater users, a court or regulatory agency could apportion the water in a groundwater basin among the overlying landowners in an amount that would ensure that no more water would be pumped out than could be recharged over time. This amount is known as “safe yield.”

These so-called adjudicated basins are fairly common in desert areas and coastal valleys in Southern California. SGMA does not override adjudications.

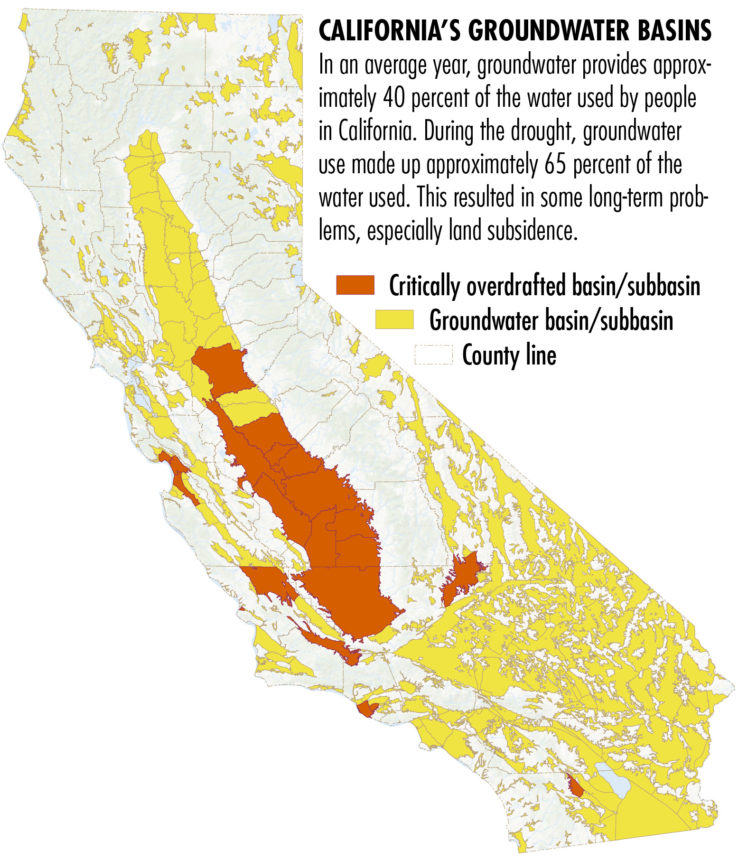

SGMA was enacted in 2014 in response to a multi-year drought. In an average year, groundwater provides approximately 40 percent of the water used by people in California. During the drought, groundwater use made up approximately 65 percent of the water used. This resulted in some long-term problems, especially land subsidence.

Land subsidence is such a problem in the San Joaquin Valley that it has caused the Friant-Kern Canal to sag in the middle, which means that it has less capacity for carrying water to orchards and farmland along the east side of the valley. Land subsidence also strains roads, building foundations, and other infrastructure. Subsidence has caused billions of dollars in damage in various groundwater basins in the state, the worst being the San Joaquin Valley. In some areas, land in the San Joaquin Valley has sunk up to 28 feet. Over-pumping also results in dropping water tables, so wells have to be drilled deeper to get to water.

SGMA is intended to result in controls on groundwater pumping that will result in having no more water pumped out than is replaced by recharge. Recharge can either be natural or man-made. Surface water can be spread out in recharge basins in wet years when surface water is abundant. These basins allow water to percolate back into the groundwater basins to replenish the water table.

Under SGMA, basins that are overdrafted have to form Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs), which will develop Groundwater Sustainability Plans. In critically overdrafted groundwater basins, the plans are due Jan. 31, 2020. In other basins, the plans are due on Jan. 31, 2022.

Most critically overdrafted basins are in the San Joaquin Valley, Salinas Valley and a few other scattered basins throughout the state. Very little of the Sacramento Valley is critically overdrafted.

In the Tulare Basin, once a vast lake and wetland, the groundwater basin is critically overdrafted. Intensive farming, including thousands of acres of recently planted almond and pistachio orchards, has replaced the former wetlands. Duck clubs mainly rely on groundwater in the Tulare Basin, because surface water is often prohibitively expensive, or just not available. Only 10 duck clubs in the Tulare Basin have any access to surface water, and they rarely get to use it.

Duck clubs in the Tulare Basin are largely within the boundaries of the Buena Vista Water Storage District in Buttonwillow, or the Semitropic Water Storage District in Wasco. Both are GSAs. In the Semitropic district, duck clubs pay a reduced “General Project Service Charge” assessment. In part, this is because duck clubs pump water onto their land, but they allow the water to percolate back into the groundwater basin. As a result, except for some evaporation, duck clubs consume relatively little of the water they pump. Farms, on the other hand, consume a large amount of water through growing crops and put relatively little back into the aquifer.

Semitropic’s draft Groundwater Sustainability Plan calls for reducing the amount of pumping gradually over time. As part of this reduction, the district intends to begin by reducing duck clubs’ pumping to no more than 1.5 acre feet per acre and gradually reduce the amount to 0.5 acre feet per acre by 2040. The duck clubs in the district usually require 3 acre feet per acre to fully flood up for a season.

In addition, all groundwater pumpers will have to pay assessments to support the activities of the GSA in developing a plan, preparing the environmental documentation, and monitoring the condition of the aquifer. Pumpers will have to install monitoring devices on each of their wells in order to determine how much water they are actually pumping.

As a result, costs of pumping water will necessarily increase and the amount of land that can be fully flooded during hunting season will be reduced. Whether duck clubs in the Tulare Basin can survive will depend on the financial resources their owners are willing to commit to covering the increased costs.

Although the Sacramento Valley is less reliant on pumping, there will be impacts there as well. Costs of pumping will rise. It is possible that the amount of water that can be pumped will be restricted.

California Waterfowl advises all duck clubs that pump water to identify and contact your local GSA, if you have not done so already. Attend the GSA’s meetings and exert whatever influence you can over the content of their Groundwater Sustainability Plans. And be prepared to pay more money for less water.

CWA will post updates in this situation to our Current Issues website. If you would like more information about the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or if you have information to share about SGMA in your local area, contact Jeffrey Volberg at jvolberg@calwaterfowl.org or 916-217-5117.